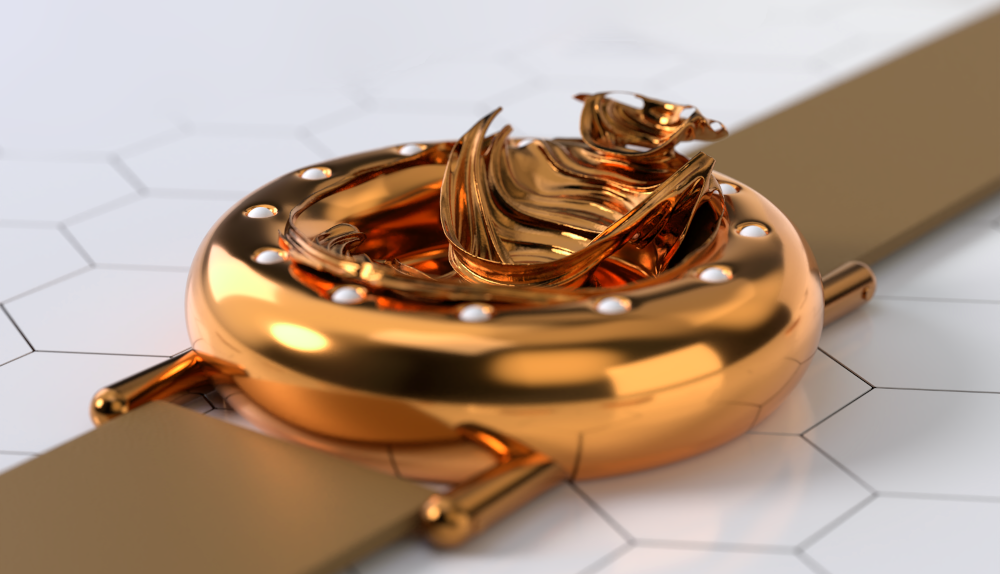

The image above shows our Poppy Seed Pod watch on the right.

Sections in this article:

- What is the Western Art Tradition?

- The Western Art Tradition and Symbolic Representations

- The Direct Complexity Revolution – The Single Conceptual Progression Behind the Development of the Western Art Tradition

- Reaching the Edges of Symbolization

- What Lies Beyond Symbols

- Perspectives on the Development of the Direct Complexity Revolution

- Is this the Biggest Revolution in the Western Art Tradition?

- Why did this Revolution Happen?

Introduction

In this article I clarify what the Western Art Tradition is, and look at what can be seen as a specific type of symbolic representations in Western music, visual arts and jewellery.

I then show you what happens when the edges of the possibilities of this type of symbolization are reached, and some of the options which lie beyond this type of symbolization (which can also be seen as systems of predefined discrete steps).

I present, in detail, the central concept of this article, which I have named the “direct complexity revolution”, with explorations and clarifications, making clear why it is arguably the biggest revolution in the Western Art Tradition, and talk about other areas it relates to. I invite your feedback on that question and on anything else relevant.

The direct complexity revolution presented in this article seems to be an entirely unique perspective. Although the points I present are likely to seem fairly obvious once you’ve read about them in this article, it seems that what I am presenting as an overall concept hasn’t been observed by anyone else at the time of writing.

I recommend you think through the points I am making and see what they add up to, from an open and neutral point of view, rather than looking from within the context of the limitations of currently accepted theory in relevant subjects.

What is the Western Art Tradition?

The Western Art Tradition, sometimes shortened to “Western Art”, (as distinct from the term “Western American Art”, sometimes shortened to “Western Art” which is art about the history of the western regions of North America) refers to the evolution and development of art forms within the cultural, historical, and geographical context of “Western civilization” (for details on that see the History of Western civilization (Wikipedia)). The Western Art Tradition encompasses a vast array of artistic movements, styles, and periods originating primarily from Europe and later extending to North America.

Although its roots can be traced to earlier times such as the great ancient civilizations of Greece (400 BC) and Rome (100 AD), the main era of development of the Western Art Tradition can be seen as being approximately the last millennium, more especially from the changes near the end of the middle ages (5th to 15th century), through Renaissance, Baroque, and Romantic periods to the great variety of modern and contemporary art movements. And it is, of course, very much still evolving as we speak.

The Western Art Tradition includes architecture, painting, sculpture, literature, music, and other forms of creative expression.

The Western Art Tradition reflects, as well as influencing, the development of cultures it relates to. One of the most significant and well-known revolutions in its evolution was the Renaissance (14th to 17th century.), which sparked a great revival in art, science, and culture, emphasizing humanism and realism, and also rebelling against the existing traditions.

The whole of the Western Art Tradition can be seen as a continual process of evolution. It constantly challenges the currently accepted norms and perspectives (while retaining some elements from the past), expanding into new areas and exploring innovative possibilities. Morse Peckham said (in “Beyond the Tragic Vision; the quest for identity in the nineteenth century”) that an artist “presents a way of escaping from some conventions.” And that (in my opinion) is a continual process.

The currently accepted view of The Western Art Tradition can be seen as being focused mostly on the details of individual art movements and relatively narrow perspectives, as can be seen from this article Western Art Theories.

While all the well-known revolutions in the arts of Europe and the North American continent are certainly significant, it seems to me that there is a single underlying concept fundamental to the whole of that evolution, which seems to be unobserved by others at the time of writing (and arguably more significant, for reasons I’ll detail below), although I think it likely that it will seem clear to you once I’ve explained it in detail during this article.

The Western Art Tradition and Symbolic Representations

Note that I am referring to a specific type of symbolic representation relating to the main concept of this article:

Symbolic representations in music.

I’ll start with music, because it’s the most obvious example of this concept.

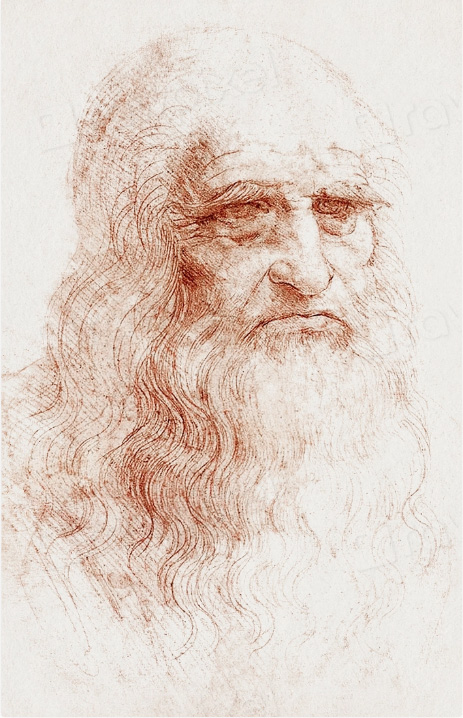

Examples of notated music go back to Babylonia c. 1400 BCE (with another example being Greek notation), with the Western staff notation (shown in the image above) appearing in medieval Europe and developing into a specific note-based system. The main focus of all these systems is the musical note.

Notes are the form that these types of music is represented in (see the image above), and they are based on a fundamental property of most “musical” sounds as distinct from many natural sounds. This property is the harmonic resonance of physical systems such as strings on a stringed instrument or columns of air in woodwind and brass instruments (most percussion instruments are resonant but with more complex harmonic systems).

These resonances (forming the concept of notes and scales, which I will explain below) are what Western Art Tradition music is mainly focused on until the early 20th century. A fundamental mathematical perspective from this same period, which is ratios between numbers, is another way to see the same thing . . .

This concept is fundamental to both the musical notation used by classical composers and to other forms of notation used in folk music or jazz, which all use the same system of notes specifying discrete pitch steps from predefined musical scales, and discrete divisions of duration.

The pitch element of musical notation, from notations used in about 1400 BCE all the way up to MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface, specified in 1983), is based on musical scales, which are themselves based on the simplest mathematical ratios between pitches.

Pythagoras (570 to 490 BCE) discovered how harmonic resonance works by dividing vibrating strings into halves, thirds, quarters etc. which resulted in scales (when harmonics were transposed down to being within the same octave). For example, the octave is the simplest ratio of the frequencies of resonances::1:2. This corresponds to a string half the length, or a column of air half the height. The pitch elements of notes use a number of discrete steps (usually 12, although in most pieces of music some of those are used more than others) within an octave (forming a scale).

The evolution of Western Art Tradition music over about the last thousand years is commonly seen as the progression of using increasingly complex ratios (as well as an increasing interest in sound more than notes). Although earlier forms of music used more notes from the scale, plainsong (originating in the first few centuries AD) was about embodying a concept of purity, using only the simplest ratios of 1:2 and 2:3. The ratio of 2:3 was even named a “perfect fifth” which reflects the conceptual perspective on it at the time.

From that point onwards, the evolution of music was a progression of making use of increasingly obscure and dissonant mathematical ratios between notes, first 3ds and 6ths (in the mid-15th century, before which they were regarded as dissonances requiring resolution), then 7ths and seconds, chromatic scales (making greater use of all the steps of the scale), and increasingly complex modulations through different keys (meaning scales with different root notes and structures).

Within this single system, used for well over a thousand years, it makes sense to represent music as notes (even while, towards the end of that period, there was increasing focus on sound more than notes). A note is a symbol for a sound, the sound itself being, in reality, very much more subtle and complex. The symbol represents only the most basic data, predefined by the system in which it is used, which in this case is about discrete pitch steps (scales) derived from simple ratios, and discrete divisions of duration.

How much is the difference in data complexity between a note and a sound? . . .

A MIDI note-on and note-off, specifying a 1 second note of a specific pitch, uses 6 bytes of information, which is somewhat more information than the same note written on manuscript (because the MIDI note contains 127 degrees of volume, compared to the 6 to 8 dynamic markings used on conventional classical music notation). The same 1 second stored as CD-quality sound uses 176,400 bytes. That is a vastly more complex data-set. To give you an idea of how much bigger that is, it would be the length of two 747 jumbo-jets end-to-end, compared to the size of a single peppercorn.

An example of music being about notes more than sounds (until recently) is piano reductions of early symphonies being obviously regarded as being the same symphony despite there being no sounds in common, because the symphony is more about the notes (and the relationships between them) than the sounds. Not that notes are exactly an absolute measurement of pitch, with the absolute pitch of the same written note having risen by about a semi-tone over the last few hundred years.

Symbolic representations in visual art.

While, at first glance, the use of the same fundamental concept of very simple symbolic data-sets might be less obvious in the visual arts, it is, in fact, present, and to a similar degree.

The main focus of what is painted, drawn or sculpted, from the earliest cave paintings, through the many stages of evolution of the visual arts, all the way to the early 20th century, can be seen as being very much about recognizable objects. These objects might be people, animals, natural landscapes, buildings or decorative objects, but they all have one thing in common: they can all be named using a few words. This is called representational art.

A word is a symbol for an object (from a language, which is a predefined set of labels).

While some views see types of “non-representational art” early in the evolution of the Western Art Tradition, such as geometric forms from the middle east or Celtic knot-work, in my view these things fit the defining factors of design more than they do art (see my unique view of the difference between art and design).

In the same way that the actual sounds produced by musicians are vastly more complex than their symbolic representation as notes, the manifested results of painting, drawing or sculpture are a vastly more complex data-set than the words which name the object(s) they represent and which are the main conceptual focus of the artwork. But the main focus for both art and music until the early 20th century. is still within the same concept: the simple symbols (i.e. predefined discrete variables).

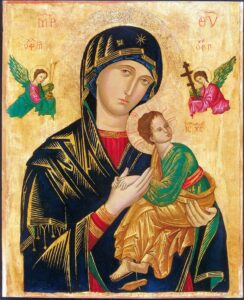

Of course, there can be more than one layer of symbolization in a painting (as well as music), as was usually the case with early art such as Greek and Roman art which used symbolism to depict mythological narratives, Medieval art employing symbols to convey theological concepts, etc. This form of symbolization is still often true later, with romantic symbolization such as lions representing nobility and tigers representing evil, or later works symbolizing political concepts. But the art through all those periods is still mostly about nameable objects, which are always present until abstract art in the 20th century, and that representational basis is a specific type of symbolism.

So both visual arts, and musical expression, in the Western Art Tradition, can be seen as being focusing mainly on things which are typically represented by predefined sets of symbols, up to the early 20th century. And, of course, literature (another art form) directly uses words, which are symbols for the objects or concepts they represent.

Fine jewellery to art jewellery. Fine jewellery, which means all jewellery until the early 20th century (except for fashion/costume jewellery which copies it with less expensive materials), and most jewellery since then, is mostly based on simple, symbolic, geometric shapes, such as perfect circles.

An example of the symbolization in fine jewellery is the circle used in engagement rings to symbolize eternity, a concept originating from ancient Egypt as detailed in the article “A history of diamond engagement rings and their timeless popularity today.“

Art jewellery often uses very complex forms and textures (such as organic, fractal or broken) as well as welcoming uses of any material. For more detail on the concepts of art jewellery, with examples, see below.

The concepts I have described above, and the major change which happened relating to these concepts around the early 20th century (which I detail below), can be defined more precisely.

Here is the definition of the core concept proposed by this article : . . .

The Direct Complexity Revolution – The Single Conceptual Progression Behind the Development of the Western Art Tradition:

Over the millennium of the Western Art Tradition leading up to the early 20th century, there was a gradual long-term increase in degree of complexity of the main focus of the work, while that main focus remained within the same systems of using relatively simple data-sets of predefined discrete representational options. After which there was an observable absolute change (detailed in the next paragraph) to the works having a main focus on a different type of systems, which is the culmination of what I am naming as the direct complexity revolution.

This absolute change is from a main focus on simplified data from a predefined set of discrete representational options, to works which focus mainly on properties similar to those of the natural world which can only be realistically represented by complex data-sets of many times the magnitude of those simple data-sets used earlier. This revolution is about both directness (symbolization being an indirect representation of more complex things) and complexity.

Notes on the definition, above:

The “absolute change” refers to the culmination of the direct complexity revolution in the early 20th century, which is the change:

- from representational to abstract art,

- from note-based music to ambient music (by which I mean music which has a main focus on sound rather than notes) (see below for a note on the timing of this change),

- and from fine jewellery to art jewellery.

“relatively simple data-sets of predefined discrete representational options” refers to notes in music which are from predefined scales, recognizable objects in visual art that there are words for (words come from a predefined language), and the simple geometric shapes that almost all fine jewellery is based on. These are “representational” (and indirect) in that they are very simple representations of other far more complex things.

This change is described as “absolute” because it is a change from use of one system (relatively simple predefined sets of discrete options) to a significantly different system (very much more complex data-sets such as continual spectra).

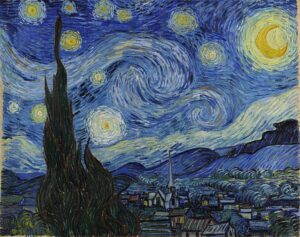

“properties which can only be realistically represented by complex data-sets of many times the magnitude of those simple data-sets used earlier” refers to properties such as continual spectra sounds or sounds with fractal properties, for example natural sounds such as the sound of the wind or a waterfall, the main focus of abstract painting for example the marks on canvas in a painting by Franz Kline (below) or Mark Rothko do not represent objects that there are simple names for, and the complex organic, rough, fractal or broken forms and surfaces often used in art jewellery (see below for more on that topic).

The name “The Direct Complexity Revolution” I chose because this significant change is about both directness and complexity. Symbolization is an indirect representation of more complex things. After this revolution artworks are more about what they are intrinsically, rather than what they represent, as well as being about vastly more complex data-sets.

I’ll give more details of this fascinating change, and the systems used after it happened, and how it relates to other aspects of society, below . . .

Known vs. Unknown Aspects of the Direct Complexity Revolution

Some aspects of this revolution (defined above) are known and detailed in other research, some aspects are, as far as I am aware, unique to my perspective on this subject.

The increase in complexity over the span of the Western Art Tradition is known in some areas of the arts:

Research into art history and quantitative analysis shows that transitions in Western art—from linear to painterly, and figurative to abstract—can be characterized by increased visual complexity and entropy. Studies using measures such as permutation entropy demonstrate how Modern Art often moves toward higher complexity. A perspective on this is “History of art paintings through the lens of entropy and complexity“.

Studies of complexity in music generally suggest a degree of increase in complexity, although a fluctuating rather than strictly linear trend in complexity and entropy over different periods. Trends in different facets of music, such as pitch, rhythm, harmony, timbre, and loudness can be different over the same period. Some studies show that, while melodic and harmonic complexity in popular music have generally decreased, the overall use of timbre (sound quality, character and instrumentation) has become more diverse and complex and is a primary focus for creative expression. This aligns with the influence from what I see as the ambient music revolution, with ambient music being more about the timbre of the sound and less about the most obvious aspects of notes such as pitch and duration and aspects of the relationships between notes such as harmony and rhythm.

The progression of using increasingly complex pitch ratios in music, from plainsong to 12-tone music, is empirically observable, and is an accepted aspect of music theory.

Aspects of the direct complexity revolution which I am unable to find mentioned elsewhere include the concept that notes in music, representation of nameable objects in art, and simple geometric shapes with highly polished surfaces in fine jewellery, are all use of similar types of symbolization, how ambient music, abstract are and art jewellery are mainly about concepts outside those types of symbolization and include a dramatic increase in complexity of what is the focus of the artwork, and that these similar changes in those three different areas of art, at around the same time (see below for my view on the timing of ambient music), are related.

Another concept I am not seeing discussed by others is that the direct complexity revolution is a significant broadening of accepted possibilities. This is discussed in individual artistic disciplines, but I am not seeing it observed as a more general phenomenon across the different arts.

Reaching the Edges of Symbolization

The visual arts developed all the way to impressionism and paintings of artists like J.M.W. Turner (below), where there can be said to be little emphasis remaining on the elements which represent objects that there are words for (i.e. “ship”). If you removed the ship in the painting below, you could see that the majority of the painting could be seen as almost abstract, and it could be said that there is more focus on the marks themselves and their interactions than on what they represent.

The marks used in the waterlilies paintings by Monet (another of my favourites) are, in my view, similarly important, making the works almost-abstract.

Music can be seen as a progression of increasing complexity, from the simplest 1:2 and 2:3 ratios used in plainsong, through increasing chromaticism (use of more and more notes from the scale), all the way to 12-tone music in the early 20th century.:

12-tone music, (dodecaphony), is a 20th-century compositional method by Arnold Schoenberg, used to create atonal music (without a key) by organizing all 12 notes of the chromatic scale into a specific order called a tone row, ensuring all notes are treated equally. The row is manipulated (transposed, inverted, retrograde, etc.) to generate all melodic and harmonic material, preventing any single note from becoming a tonic. This strict structure produces atonality, moving away from traditional harmony with its focus on one note as the basis of the harmonic system.

So where can you go from there? . . .

What Lies Beyond Symbols?

. . . beyond symbols are continual spectra sounds, marks which don’t represent objects, and other complex data-sets which are appreciated as what they are instead of understood as what they represent.

Seeing the progression of about the last thousand years of Western Art Tradition music, from plainsong, as use of increasingly complex relationships between the 12 notes of a conventional scale, once you’ve progressed all the way to 12-tone (which uses all 12 notes equally) and microtones, there’s one obvious place to explore in terms of continuing the progression of increasing complexity.

The development of Western Art Tradition music can also be seen as a gradually increasing emphasis on sound rather than notes (which is also an increase in complexity, since sound is a much more complex data-set than notes).

In painting, it seems to me that there is an increase in emphasis on the more complex data-sets which is the marks themselves rather than the named objects represented, after its development has progressed to leave almost no emphasis left on the objects which can be symbolized (named), there’s one obvious place to explore in terms of continuing the progression of increasing complexity.

An obvious way to continue the same progressions of increasing complexity, in both music and art is to cease using those sets of symbols (predefined discrete items) entirely . . .

This part of the journey is easier to see in the visual arts. It is abstract art, where the marks made are not used to represent a nameable object at all. A famous example of early abstract art is the Kandinsky watercolour below, which might have been painted in 1912 or 1913 then backdated to 1910. Other artists producing abstracts at around the same time include Hilma af Klint (creating abstract works from about 1906) and Malevich, with Mondrian painting his well-known abstracts from 1914..

Other abstract artists such as Franz Kline (1920 to 1962) used marks which are themselves complex and fractal in nature:

Music beyond notes: At around the same time as abstract art was arising, avant-garde music was moving deliberately beyond the convention of notes to a focus on sounds themselves, which can be seen as a culmination of the increasing emphasis on sound more than notes approximately over the previous thousand years. An example is “4′33″ by John Cage (written in 1952), where the performer walks onto the stage, opens the lid of a piano, sits there without touching the piano for four minutes thirty-three seconds, then closes the lid of the piano signifying the end of the piece. So the music is the sounds in the concert hall during that time, with not a single note being used in the representation of that piece of music.

John Cage says “Each aspect of sound (in modern music), frequency, amplitude, timbre, duration, is to be seen as a continuum, not as a series of discreet steps favored by convention” (from Silence: lectures and writings. Cambridge: The MIT Press (1966)), which, from my perspective, points out the profound difference between the discrete steps of note-based music and the continual spectra present in most natural sounds and present in most ambient music.

Another example of music beyond notes is “music concrete” (such as Pierre Schaeffer’s Cinq études de bruits (Five Studies of Noises) from 1948), which uses recorded sounds which cannot be represented effectively by musical notes (such as the sound of the wind, or a waterfall), to construct a piece of music.

Of course, there were other genres of music at around the same time (and after that period) which still used notes, such as aleatoric music and spectralism. However, in terms of complexity of relationships between notes, those can be seen as being somewhat less complex than 12-tone music with its fully equal use of each note of the scale. A specific genre: “New Complexity” in contemporary classical music in the late 1980s (as detailed in this Wikipedia article) specifically denotes a movement where composers use increasingly intricate structures, notations, and sound techniques, directly contrasting with “New Simplicity”. However, the music of those genres is still mostly defined by notation, even though the notation can include microtones as well as using unconventional instruments and tunings.

By contrast to use of notation, ambient music (by which I mean music which has a main focus on sound rather than notes) is something significantly different in terms of increase in complexity, focusing mainly on an entirely different system: that of continual (or fractal) spectra rather than the discrete steps of notes. So ambient music can be seen as the most significant step forward in terms of the perspective of the millennium of Western Art Tradition music as progression of increasing complexity first using more complex relationships between notes then moving to a focus beyond notes.

Since a continual spectrum is, by definition, continual, it can be divided as finely as the viewer chooses to look, so the potential degree of complexity is infinite. This can be seen in fractal zoom videos, where however much you zoom in there is still just as much detail and always further you could zoom in. This is not just a difference in degree within a system of discrete notes (however many notes there are in a specific system ), it is a fundamental, absolute difference. While to be precise this is potential infinity, since it would take an infinite amount of time to explore or manifest the whole potential data-set.

Improvements in technology were a significant part of the ambient music revolution, both for the classical route such as music concrete (using recorded sounds from the real world as raw material for editing), and for the non-classical route, allowing recording and manipulations of sound, from subtle changes in character to profound alterations and entirely new creations.

Ambient music can be seen as arising at around the same time in both classical and non-classical music, via somewhat different conceptual progressions (although both involve letting go of some elements, and use of new technologies), with there being some degree of influence between the two.

My Master’s Degree thesis is about: The Beginnings And Implications Of Ambient Music.

The two areas of abstract art and contemporary music influence each other, as noted in papers such as “The Influence of Abstract Art on Contemporary Music“. While I see some truth in this assertion I also see that it is mainly the result of the specialist’s view of narrow areas of the Western Art Tradition by contrast to the overall systemic view presented in this article. From my wider perspective, yes, they influenced each other to some extent, but there are more significant underlying factors which resulted in the same major changes to both of them (I make some comments about the causes of all this, below).

This same major revolution happening in all the arts at the same time (see the paragraph below), as well as in different branches of musical exploration, is, in my view, not really a coincidence.

When was the ambient music revolution? While some sources state that ambient music originated with Brian Eno’s music in the 1970s, which aligns with when it was recognised as a distinguishable genre and labelled “ambient music”, it seems to me that the definitions of the concept of ambient music is such as where the sound is more important than the notes, and the music not necessarily being the main foreground focus, show its emergence to be more gradual, including such pieces as Erik Satie’s “musique d’ameublement” (furniture music) for background listening in the early 1900s. Which is clearly around the same time as abstract art, with Hilma af Klint painting abstract pieces around 1906, then Wassily Kandinsky creating his first abstract works around 1910-1911, and around the same time as art jewellery was emerging (although that started slightly earlier).

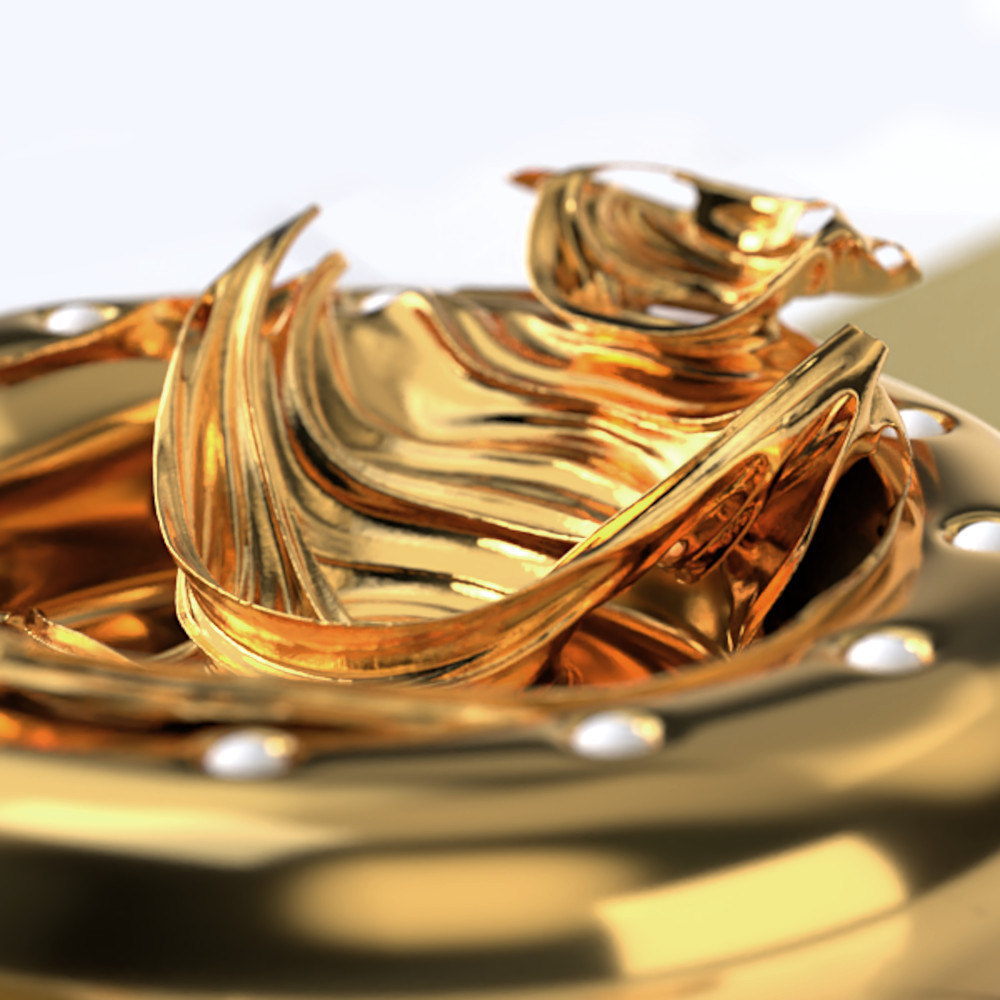

Art jewellery can be seen from the same perspective, as a fundamental change from the simple, symbolic forms and highly polished surfaces of fine jewellery to vastly more complex forms and textures including organic forms and rough, fractal or broken surfaces.

Art jewellery also clearly shows how this revolution is also a change from things trying to represent other things (which is what symbols do), to things being about what they are intrinsically and directly, so forms and textures are accepted as what they are in art jewellery instead of trying to disguise them (such as by polishing) or decorate them. This relates to authenticity, transparency and openness, as well as to the Japanese principle of wabi-sabi which finds beauty in imperfection and transience. Here are some examples of art jeweller, showing the use of complex and authentic forms and textures:

As with other art forms, discussions of art jewellery point to the rise of digital and AI tools managing vast aesthetic data, with artists like Refik Anadol utilizing algorithmically processed data sources to create new forms of abstraction. So it seems to me that there is some observation by other researchers of increasing complexity but little understanding of the overall major shift from simple symbolic forms to the fundamentally different basis of much more complex forms and surfaces.

How much is the degree of increase in complexity from before to after the direct complexity revolution?

The systems which can be seen as the focus of the arts before this revolution, include notes in music, paintings about nameable objects, and words used in literature.

The continual spectra used after that change often have fractal characteristics.

How much difference is the data-set of a fractal zoom compared to keys on a piano?

The deepest fractal zoom (a 24-hour long “world record attempt” by the YouTube channel Maths Town), zooms in to a magnitude of a number that is 1 followed by 21,831 zeros. That is an example of just part of the data available from a fractal object.

By contrast, most piano keyboards have 88 notes, which is a data-set of a magnitude which has just a single zero. Words used in literature currently number around 170,000 (data from the Oxford English Dictionary) which is a magnitude with 5 zeroes, and only a small sub-set those are objects which are the focus of representational paintings.

Each zero in a magnitude means ten times bigger.

An analogy of the degree of difference between words used in literature and the data-set from that fractal zoom, would be the difference between a single drop of ink used to write the digit ‘1’ and a library so large that it would not fit within the observable universe just to hold the paper needed to write all of the zeros, one after another.

The progression of the Western Art Tradition makes art further from design.

The direct complexity revolution can be seen as exaggerating the differences between art and design.

The cause of the differences between art and design can, in my (unique) view, be summarised as:

| Art | Design | |

| Focus | intrinsic | extrinsic |

| Aim | unknown | known |

For details on how, in my opinion, those simple factors cause all the more commonly known differences between art and design, see my comments on The Difference Between Art and Design.

Abstract art and art jewellery are more about what they are (i.e. intrinsic and authentic) rather than what they represent, compared to figurative art (which represents objects you can name) and fine jewellery (which uses simple symbolic representations and highly-polished to represent a perfect ideal rather than complex reality). They are also more clearly about the unknown as they move from a focus on use of predefined (i.e. pre-known) sets of symbols to vastly more complex fractal and continual-spectra realities (fractals being on the edge of chaos, i.e. the unknown and unpredictable), most obvious in the development from note-based to ambient (non-note-based) music.

Limited perspectives. The same relatively narrow basis of perspectives is, in my view, seen in discussion of the development of the Western Art Tradition.

For example, the digital humanities revolution enables art historians to analyse vast databases of artworks, with computational art history addressing issues of data-set size and complexity, especially in algorithmic analysis and critique of Western canon datasets.

Other views include permutation entropy and statistical complexity being used to assess the evolution of art across periods, showing transitions in art history as movements between different degrees of order and complexity, demonstrate clear trajectories in a complexity–entropy plane that map to major art historical periods, such as the transition from representational to abstract art, and from Modern to Postmodern. This is discussed in Sigaki, H.Y.D., Perc, M., Ribeiro, H.V. — “History of art paintings through the lens of entropy and complexity” (PNAS, 2018). While this is, to some degree, a view of increasing complexity, it is, as far as I am aware, not seen as affecting other arts, and not presented as an underlying and overarching factor over the whole progression of the Western Art Tradition.

Related ideas come from digital art analysis, Western bias, and art curation. Similar methods and perspectives are applied to the development of music.

However, all these current scholarly perspectives seem to me to be based on relatively narrow views of specialist areas, with apparently no-one seeing the overall underlying concepts I present here that apply to all the arts (and to relevant cultures) simultaneously. These conclusions by other researchers show that others are seeing some of the effects of what I am presenting here, but this article, uniquely, posits an overall perspective of those effects.

Perspectives on the Development of the Direct Complexity Revolution

Parallels with the development of artistic ability. The development of the Western Art Tradition can be seen as being conceptually similar to the development of a child that grows up to become an artist. Children start with art as symbols only. If you ask a young child to draw a person standing in front of them, they don’t look at the person, they draw a symbolic representation from their mind.

This was understood from the 1950’s, where stages of the development of children’s drawing were recognised, such as the pre-schematic Stage (4-7 years), where the child first attempts to symbolically represent something from the reality, usually beginning with a very simple symbol for person. More details on this from “Children’s Artistic Development: An Overview”.

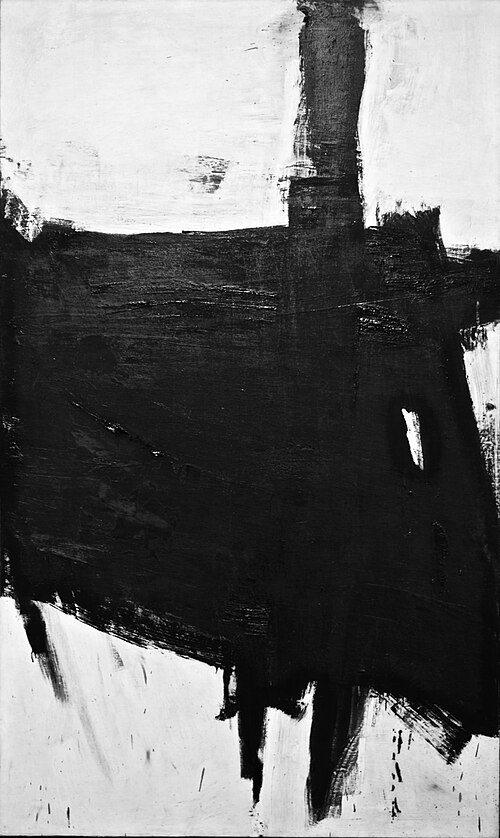

It is only later that some people, if they learn to be artists, draw from what they see directly with their eyes, in all its complexity (as can be seen in the Da Vinci drawing below), instead of using much simpler symbolic representations.

Drawing reality instead of symbols. Finding ways to do this effectively can make a big difference to the aesthetic quality of the results. For example, if you draw a copy of a photo of a face, the results might be OK. But if you turn the same photo upside-down then copy it, the results are usually much better, because you are more likely to draw what you actually see rather than being influenced by the symbolic aspects of what you are recognizing as you look. I read about this in the excellent book “Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain” by Betty Edwards, which was from the reading list before I started my Art Foundation course. (More on my development as an artist, here).

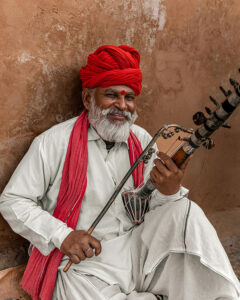

The Western Art Tradition and the emotional curve. The concept of this article, as an overarching change after a period of continuous development with short-term developmental stages, also relates to the fact that music in the Western Art Tradition is fundamentally about the emotional curve: with beginnings, developments, climaxes and endings, i.e. things that change and relate to each other over time as I see the whole of the development of the Western Art Tradition doing. This idea of the emotional curve was first systematically explored and explicitly discussed during the Romantic era (roughly the 19th century), but applies to most Western music before that, and to an increasing extent as classical music develops, until it is sometimes ignored entirely after the direct complexity revolution.

This is completely different from traditional Indian music, for example, which can be seen as an excerpt from something which could have been going on for an infinite amount of time before the excerpt you heard, and continuing for an infinite amount of time afterwards, with no change in emotional intensity over time.

The whole thousand-year progression of the direct complexity revolution can be seen as an emotional-curve with a beginning, a progression, and a climax around the early 20th century.

Differences between art and design. This concept can also be said to strongly relate to The Difference Between Art and Design, and to the fine art process. Design is creating something in your head, then manifesting that into material form and the process is complete. The fine art process, as I see it, fundamentally includes comparing your manifestations with objective reality, in an iterative manner, although not everyone agrees with this definition. The implications of this difference are profound if you understand that what is stored in a mind can only be symbols, i.e. thoughts and simplified models of reality, not the much more complex realities they indirectly represent (it is considered a fundamental principle in cognitive science, psychology, and philosophy that thoughts are often represented as internal symbols, often referred to as mental representations).

Relationships with the world. The development of the Western Art Tradition can also be seen as being part of cultures which can be seen as going from living a strongly integrated part of dangerous, challenging natural world, through about a thousand years of taming and distancing from nature, through people moving into towns during the industrial revolution and thereby feeling more isolated and protected from the dangers of the outside world, and only after that, choosing to go back into nature (objective reality in all its complexity) and seeing it as beautiful and valuable in its own right rather than just a resource to be exploited without concern, or dangers to be avoided.

The arts after the direct complexity revolution can be seen as celebrating reality in all its complexity and imperfection, compared to those before it which are separated from reality by simplification and symbolization. Symbolization is, as well as being about simplification, can be seen as a distancing from the complexity and challenges of the natural world, i.e. it is indirect.

Religion and the arts. During the majority of the development of the Western Art Tradition, religious perspectives dominated society, with their perspectives dominating the arts, and can be seen as being involved in avoiding the natural world where possible, considering the natural world as evil and as there only for heedless use by humans who should have most of their attention on things outside this world such as conceptual ideas about higher realms. So this relates to the point I made in the above section of this article about relationships with the world.

Left and right brain hemispheres. The idea that the left brain hemisphere uses symbolic representations such as logic, language, and analytical thought and that the right brain hemisphere works with more complex and subtle data-sets such as creativity, spatial processing, and emotional intuition, is not about fully separate functions of physical brain hemispheres. These two different ways of functioning are now considered not to be used by each hemisphere of the brain exclusively, and in reality have more of an integrated function.

However, the difference between the two types of functioning is still valid, and, obviously relates significantly to the direct complexity revolution, as follows:

The progression through the Western Art Tradition reflects what I see as the “Western World’s” over-emphasis on the “left-brain” aspects throughout most of its development, with somewhat increasing focus on “right-brain” aspects from the 20th century.

Similar changes outside the arts

At a point during the progression of the Western Art Tradition, and the cultures it developed in, the natural world began to be seen (from an external perspective) as having value in its own right, as worthy of really looking at, rather than just seen as nameable objects, and as being represented as worthy of interest in its own right, in the arts (although a less common focus on nature as a subject was present before this).

At the same time as abstract art and ambient music breaking free from the conventions of redefined symbolization, societies were offering a very much wider range of options and sub-cultures.

While the revolutionary concept of valuing the natural world in its own right, and seeing it for what it is rather than just recognizing the symbols in it, were certainly a major shift at the time, these perspectives also relate to ancient concepts. For example, in Taoism one will learn the difference between just labelling things (i.e. symbolization) such as “that’s a sparrow” which means you then don’t look at what it actually is any more, compared to really looking deeply and directly at all the details, complexity, beauty and wonder of the reality of the object itself.

Another somewhat related phenomenon is that most people are specialists these days, since the industrial revolution. This is in contrast to Eastern traditions where one was trained in a range of different areas such as martial arts, philosophy, painting and calligraphy, music, poetry etc. with each of those areas seen as relating to the others. A similar concept is the “renaissance man”, meaning someone skilled in a diverse range of areas. It seems to me that specialists are more likely to be looking via the accepted reality of their specialism, compared to a generalist who is more likely to see the underlying relationships between different areas, which is a somewhat more direct view, as I have used in noticing this revolution.

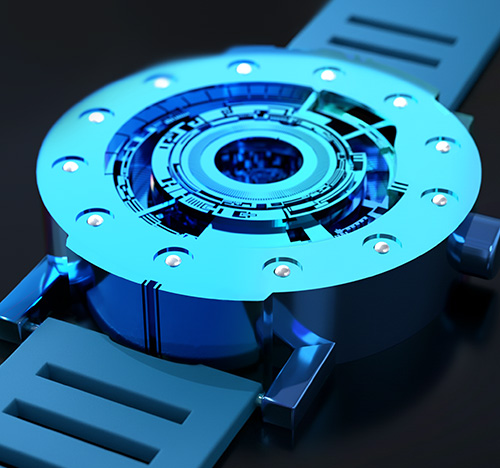

Most natural reality has fractal properties (although over a limited range), and is made of continuous spectra (not divided into simple discrete steps). Human technology has so far focused mostly on much simpler non-fractal forms and concepts, and aspects that can be broken into simple discrete steps. Fractals are now starting to be used in technology, as well as having been used in the arts from the mid-80’s, as I detail in my article on Fractal Art. An example of fractal art is my Fractal Emergence watch, shown below, which arose out of my long-term artistic obsession with fractals, which I had explored both from a fine-art perspective and in terms of contemporary music composition and non-note-based sound synthesis:

In abstract art, the focus is often on the complex, fractal aspects of the marks made and the interactions between them, in their own right, and the resulting structures and relationships, not just as an often barely noticed part of the representation of a symbol like the beautiful clouds in a painting of a recognizable landscape.

A similar change is seen in the development from fine-jewellery with its simple geometric shapes, to art jewellery, which often uses complex (non-symbolized) organic forms and deliberately rough, fractal textures, and is often created by an individual as a personal artistic exploration (which is part of the definitions of art). Below is an example of this: one of our unique conceptual-art-jewellery-based watches, using complex, non-symbolized organic forms (based on a poppy seed-pod), and the deliberately rough texture of unpolished blackened silver of a 3D printed and cast object:

If you are interested in our watches . . . subscribe to our Priority List for launch notifications.

Is the Direct Complexity Revolution the Biggest Revolution in the Western Art Tradition?

Yes it is arguably so, for two main reasons.

Firstly, while the many commonly-known revolutions in the Western Art Tradition are significant, the change from more than a thousand years of fundamental focus on a specific type of symbolization across different modes of artistic expression, to moving beyond that whole conceptual system, is, in my view, clearly a significantly bigger revolution. It’s an absolute change of system used, which is on a more senior hierarchical level of change than gradations of development within the same system.

And secondly. it’s also a revolution which can be seen as applying, in terms of its clear causal progression, over the whole of the time-line of the last thousand years of the development of the Western Art Tradition, such as the continual development of music from plainsong to 12-tone to ambient as a single progression of increasing complexity. Although the climactic absolute change was around a fairly specific period, the climax cannot be separated from the gradual long-term development which led to it. Most of the other revolutions in the arts apply only to relatively short time periods.

What do you think about these concepts? I’d love to know your personal views on this (add your comment below or on our social media).

The thesis of this article, the direct complexity revolution, can be seen as a “grand unifying theory”, or a proposed overarching framework, of the overall development of the whole Western Art Tradition.

Why did this Revolution Happen?

While there are several different factors which can be seen as causing the direct complexity revolution, one of the most significant factors is the change in the main focus of the lives of the majority of the developed world from basic survival to self-expression and thus, to some degree, from what is provided and agreed by society, to what is available in the outside world.

One well-known view of the hierarchy of needs is from Maslow. He originally proposed that the lower needs have to be met before higher needs will be focused on, then in 1987 he clarified that these levels are not as rigid as that, and are to some degree more inter-related:

| Need Level | Description | Examples |

| 5) Self-Actualization | Achieving one’s full potential and seeking personal growth. | Personal growth, creativity, problem-solving, skill development, and peak experiences. |

| 4) Esteem | The need for self-esteem and respect from others. | Self-worth, achievement, independence, status, prestige, and recognition. |

| 3) Love and Belonging | The need for interpersonal relationships and a sense of connection. | Friendship, family bonds, intimacy, affection, and being part of a group. |

| 2) Safety | The need for security and protection from physical and emotional harm. | Personal security, financial stability, health and well-being, and a safe environment. |

| 1) Physiological | Basic biological requirements for human survival. | Air, food, water, shelter, warmth, clothing, sleep, and sex. |

As the “Western world” developed, increasing numbers of people were able to focus more on the upper levels of this sequence. This results in increased focus on self-expression for a larger percentage of the population (which is one of the definitions of art which I detail in my article “Are Watches Art?“).

A 2022 study (Change in Maslow’s hierarchy of basic needs: evidence from the study of well-being in Mexico) using data from 850 participants found that love and belonging needs were the most crucial predictors of life satisfaction, challenging Maslow’s order which places physiological and safety needs as the primary foundation. In my opinion, what this conclusion might not be showing clearly is that by 2022 most of the participants in that study would have taken basic physical survival and security for granted, so they might still be the “primary foundation” necessary for higher levels, but are no longer what people consciously focus on.

A survey of people in an area at a time of significant famine or war (or any time more than a few hundred years ago, where both of those factors were significant for most of the population), one might find that the participants were much more consciously focused on basic physical survival and safety as the subjective “primary foundation” that they were most consciously aware of.

It could also be seen that, in today’s societies in the developed world, someone more focused on the 4th and 5th of Maslow’s levels would be more likely to receive love and belonging, because others who want those things admire them more than someone focused consciously on physical survival. And, as has been well documented (such as in the paper: Being More Educated and Earning More Increases Romantic Interest), there is a clear correlation between a man being able to provide more value (for survival and safety as well as other levels.) and his desirability in relationships. In my opinion, being able to provide more value would also increase the likelihood of being successful at receiving love and belonging and having more time to focus on esteem and self-actualization. As Maslow realized some time after he had initially published his theory, the different levels are significantly interrelated.

These changes in conscious aims can be seen as resulting in less focus on what is commonly provided and agreed by society, allowing increasing uniqueness and self-expression utilizing what is available in the outside world and one’s own personal relationships to it. The lower levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs are more likely to be implemented by a group, compared to the upper levels which are more about individuals. So that facilitates a change from using simple systems already agreed by the culture one is in, to being able to use anything from objective reality (such as more complex systems) as well as from any culture and perspective. As I mention in my article on Uniqueness: how the concept has changed through history, almost all people still use what society provides for their needs, but the basics of life such as physical survival are now so taken for granted that other aspects of life can be prioritised in terms of conscious attention, which shifts the focus of society more towards the higher levels of Maslow’s needs such as self-expression.

So, in my view, the change in the conscious focus of society from group-based survival to individual expression can be seen as, to a degree, relating to (and facilitating) how the direct complexity revolution is a change from use of predefined symbols agreed by a culture (i.e. group-based), to use of non-symbolized (non group-based), and far more complex, continual spectra.

There are much wider possibilities once one leaves the constraints of predefined symbols, so the results of using continual-spectra and complex data-sets are intrinsically likely to be personal and unique to a greater degree.

The direct complexity revolution in the Western Art Tradition happened simultaneously with the fracturing of relevant cultures from essentially a mono-culture to being much more about a wider variety of small sub-cultures, as well as a dramatic increase in the rate of change. This is not a coincidence, since the same factors, as outlined in this article, apply to both at around the same periods of history.

This major change to a wide variety of sub-cultures in societies as a whole was itself partly caused by factors including:

- modernization and social movements,

- reaction against mass culture and commodification,

- technological advances and the internet,

- globalization and social media,

- immigration and multiculturalism.

. . . as well as by the influences I outline above.

The causes of the direct complexity revolution are complex and interrelated, but seem to me to relate to a significant degree to what I’ve outlined in this section of the article.

How and why I discovered this perspective:

Why was it me who discovered the unique perspective from this article, almost by accident, while briefly exploring how my unique watch brand relates to other things, rather than other researchers who dedicate their whole lives to investigating in these areas?

I am unusual in the context of the extreme specialization common in the developed world in that I am a generalist (as well as having specialisations in creativity and advanced empirical spirituality), which significantly facilitates seeing such overarching and underlying perspectives on such things by relating different perspectives and conceptual starting-points. This was also an important factor in how I created my very unique brand of timepieces (below), which are not an extension of the watchmaking specialism like most other unusual watches, but are, instead, arguably the first melding of fine art sculpture with the much more ancient 12-point time-ring principle.

I have been described as “a renaissance man” by one of my creative colleagues, since I am more of a generalist than most people in today’s society. This also aligns with ancient Eastern perspectives about learning and personal development, where one would study martial arts, calligraphy, poetry, spirituality, philosophy etc. as a set of inter-related subjects.

I have always been interested in the underlying causes beneath how and why things are the way they are, initially from scientific and philosophical perspectives, then later as the basis of my unique research and practice of advanced empirical spirituality, which itself further increases my ability to see such things more clearly.

Being a generalist is one of the main factors behind me creating the ongoing artistic explorations of this brand, because generalists can more easily explore new relationships between different disciplines, such as fine art and an ancient horological principle, as I did for these watches (below), than specialists can.

In case you’re reading this article and haven’t yet noticed how it relates to our unique watches (below) . . . we’re arguably the first conceptual-art-jewellery-based watch brand. Which makes us part of the direct complexity revolution I outline in this article.

Some of our watches obviously use organic forms (including 3D fractal forms, such as in one of the examples below) and some use deliberately rough, complex textures like blackened silver, which makes them art-jewellery (not fine jewellery).

Each UnconstrainedTime watch is by an individual creator focusing on chosen aesthetics (rather than conventional symbolic forms, mechanical engineering influences, fine jewellery, or strongly archetypal time-displays). And our watches are also offered as small numbered releases (as fine art can be) and each can be personalised by your choice of metal. These factors are some of the definitions of art,

And . . . our launch watch can be seen as being even more obviously part of the direct complexity revolution, being probably the first ever watch based on a 3D fractal (which is a very complex data-set) . . .

If you find our watches interesting . . .

Don’t miss our launch!

. . . make sure you subscribe to our Priority List for notifications.

We welcome your comments on this article, and/or on our social media channels (see below) . . . do you think what I have described in this article is the biggest revolution in the Western Art Tradition, or not, and for what reasons???

Author: Chris Melchior

This article was authored by Chris Melchior, founder of UnconstrainedTime and creator of the original range of wrist-worn sculptures of this unique artistic adventure.

Chris has extensive knowledge and experience of creativity, including fine art and cutting-edge contemporary music composition, and was awarded a First Class Honours Degree in fine art and music, with a minor in philosophy, from a leading UK University.

Chris’s life-long artistic obsessions include organic forms and textures, abstraction, fractals, and the aesthetic essence of musical genres.

He has developed unusually deep insights into the elemental concepts underlying areas including Eastern and Western philosophies, science and technology, creativity and the arts, as well as advanced empirical spirituality in which he is acknowledged as a leading authority.

He has a profound fascination and love for the unique and synergistically creative combination of fine art with the ancient essence of time-keeping which evolved into the UnconstrainedTime project.

Leave a Reply