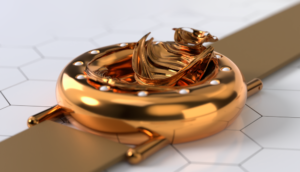

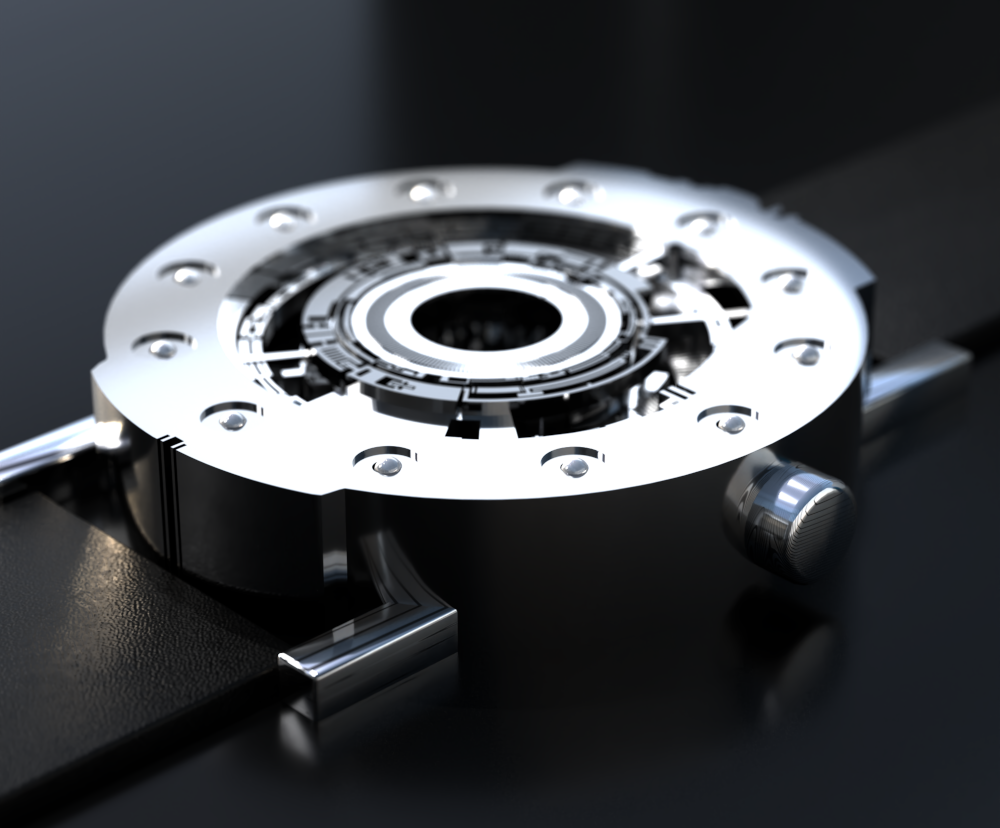

The image above shows our Fractal Emergence watch top right.

Sections of this article:

- Factors Causing The Evolution Of The Watch

- The Evolution Of The Watch Through History.

- The Evolution Of Watch Marketing

- Factors Behind Contemporary Watch Design

Introduction

How watches have changed over time is a fascinating subject. As I usually do in my blog posts, I like to look a little deeper into the evolution of the watch, examining not only the significant events, but the factors which caused that intriguing development through the history of horology. I also look at how all of this relates in fascinating ways to our own watches, at the end of this article.

Note . . . I only use watch images with permission from the watchmaker (unless the photos are public domain or creative commons), so some of the watches I present here might be lacking an image.

Factors Causing The Evolution Of The Watch

There are two main factors causing the evolution of the watch:

- the market

- technical innovation and development.

These two factors each affect the other, with the needs of the market driving technical development (we’ll see a great example of that, below), and technical innovations changing and disrupting the market (as it did significantly in the ’70’s). I’ll detail how both of these factors drove the evolution of the watch, below, as well as looking into the factors involved in contemporary watch design.

Watches have always been designed for people to purchase, although more recently some unusually innovative timepieces can be seen as a personal creative exploration (see some interesting examples of that, below).

Although watches have been mainly a functional item throughout most of their history, wristwatches (as opposed to pocket watches) actually began as decorative items for women, and were very inaccurate at that time. Later, wrist watches for men originated for very practical reasons (see below), then, more recently, became more focused on aesthetics, story and other factors. I’ll explain the reasons behind each of those, below.

There have been many significant advances in the technology used in watches. Each major innovation has allowed new opportunities for selling timepieces.

The Evolution Of The Watch Through History.

The concept of measuring time has been an intrinsic part of human civilization since ancient times. From the sundials of ancient Egypt:

. . . to the highly sophisticated smartwatches of the present day, the evolution of timekeeping devices, particularly watches, has been a testament to human ingenuity, desire, and technological advancement. This exploration of the history of watches unveils a fascinating journey through centuries of technological innovation, marking pivotal milestones that transformed timekeeping from a practical necessity to an artful fusion of craftsmanship, precision engineering, and fashion.

Ancient Beginnings: Sundials and Water Clocks

The quest to measure time began with rudimentary methods, and one of the earliest known timekeeping devices was the sundial. Ancient civilizations, notably the Egyptians and Babylonians, utilized sundials, which relied on the sun’s position and casting shadows to indicate time. These early timepieces were significant in terms of shaping the perception of time and organizing daily activities.

Another significant invention was the water clock, also known as a clepsydra. Developed by civilizations like the ancient Greeks and Chinese, these clocks measured time through the regulated flow of water. Despite their limitations, these devices marked a crucial step in the evolution of timekeeping technology.

The Advent of Mechanical Watches: From Clocks to Wearable Timepieces

Clocks were invented by blacksmiths in the 14th and 15th Centuries, who used their experience in working metal to create timekeeping devices which announced the time using bells.

Mechanical clocks became a status symbol, both for individuals and for towns and cities where clocks were prominent landmarks. An examples of this is the beautiful Prague Astronomical Clock (made in 1410), the most famous clock from the Medieval period, shown below:

The transition from stationary timekeeping devices to portable ones marked a significant leap forward. During the 15th century, clockmakers miniaturized wall clocks, giving rise to the first portable timepieces. Early mechanical “clock-watches”, often worn as pendants, were ornate and primarily accessible to the affluent, worn as ornaments and not really used for telling the time because their accuracy was so poor, often gaining or losing several hours per day. At that time, the prestige of owning one of these innovative devices was an important social factor. And aesthetics was the main focus, as is the case with many watches today, despite the vastly improved accuracy of current examples.

The first portable watches were heavy drum-shaped brass boxes, with a diameter of several inches. They typically had a hinged brass cover (no glass), decoratively pierced so that the time could be read without opening it, and were often engraved and otherwise ornamented. Their shape evolved into a more rounded one, which were known as Nuremberg eggs.

The iron or steel movement, often including bells or alarms, was held together by pins and wedges until screws took over this function by the mid-1500’s. In this era, a watch would usually need to be wound twice a day. The market evolved to include a trend for watches with unusual shapes, including ones shaped like animals, stars, insects or even skulls.

Peter Henlein (1485-1542), a German locksmith from Nuremberg, is often credited with creating the first pocket “clock-watches”, which were mainly ornamental timepieces worn as pendants, the first type of timepieces to be worn on the body.

Other sources point to the fact that there was an earlier reference in 1462 to what was then called a “pocket clock”, in a letter from Italian clockmaker Bartholomew Manfredi.

The word “watch” used for timepieces originated from the word “watch” referring to a period of duty, for either town watchmen or sailors. The Oxford English Dictionary shows the word being used in association with timepieces from 1542.

The origins of Wristwatches and Pocket-watches

The evolution of the watch continued, with early wrist watches being worn initially by high class women such as Elizabeth 1 of England, who was given one (described as an “arm watch”) in 1571, and were made to be more decorative than functional (their accuracy was very poor). During that period of history women were expected not to know the time.

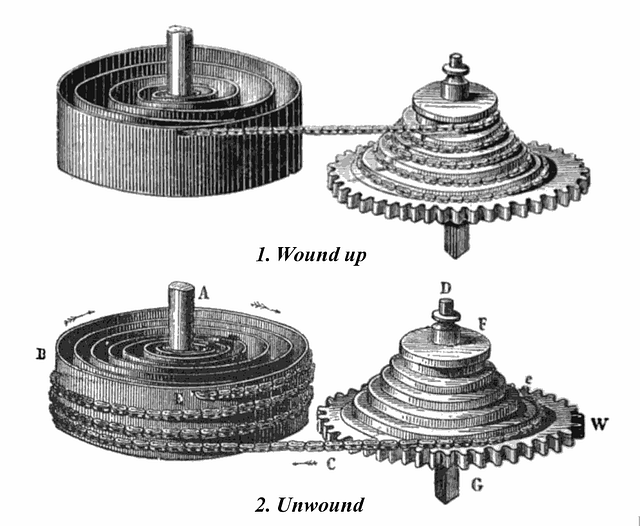

The 16th and 17th centuries witnessed remarkable technological advancements in watchmaking, notably with the introduction of the mainspring, replacing the reliance on weights for power as had been used in clocks. But, the use of a mainspring also resulted in timekeeping errors not present in clocks powered by weights. These errors were reduced by the use of a fusee:

. . . which is a curved conical pulley with a chain wrapped around it which attaches to the mainspring barrel, which results in a change in the force as the spring unwound, and soon became a common feature in watches.

The mid 1500’s saw the origins of the Swiss watch industry, with innovations including use of materials such as brass, bronze, and silver. One major factor in that country was the ban on jewellery by reformer John Calvin, so that jewellers had to learn a new trade to earn a living, and turned to watchmaking.

In the 17th Century, men started wearing watches in their pockets, which led to the design of the pocket-watch having smooth rounded edges:

This change to pocket watches was not just a matter of style, since keeping a watch in a pocket helped decrease the problems that the weather would cause for watches worn as pendants. Another factor in the popularity of the pocket watch was the popularization of the waistcoat as a common fashion item by Charles II of England. Some pocket watches included glass faces from 1610. These watches were wound by opening the back and using a key.

This image shows the movement, including balance spring, of a watch made by Thomas Tompion in about 1677:

A big improvement in accuracy came from another technological innovation, the balance wheel, included in some watches from 1657.

These early devices were usually powered by winding a mainspring which turned gears and which in turn moved the hands. The timekeeping function used a rotating balance wheel.

As accuracy of watches improved to around ten minutes per day, the minute hand was added to some watches, starting in 1680 in England. Pocket watches were an important part of the wardrobe of well-off gentlemen by this time.

The perspective of watches and clocks as scientific instruments, during the “enlightenment” period (starting 1685) resulted in significant technological improvements. For example, accurate clocks were desperately needed for navigation at sea, for naval battles and long-distance voyages. This led the British government, in 1714, offering a longitude prize for a method of determining longitude out of sight of land, with the awards offering the equivalent of $2.5 million to $5 million in today’s terms. This great example of the needs of the market driving technical development resulted in much more accurate timepieces called marine chronometers, such as this example by John Harrison (between 1761 and 1800. Great Britain.):

At this point in history the best watches took time to build. For example, it took Harrison (one of the most famous watchmakers ever) six years to build his first “sea watch”, now known as H4 (shown above), which at 130mm in diameter was about twice the size of most pocket watches. It was made specifically for the Longitude prize.

Improved Precision and the Industrial Revolution

The pursuit of precision and accuracy in timekeeping led to significant innovations in watchmaking techniques during the 18th and 19th centuries. The Swiss, already renowned for their watchmaking expertise, played a pivotal role in advancing the mechanical watch industry.

A wristwatch was made, in 1810, by Abraham-Louis Breguet for Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples. In 1868, Countess Koscowicz of Hungary had what was called a bracelet-watch made for her by the now famous Patek Philippe. Wristwatches were initially considered a feminine accessory and marketed as bracelets or wristlets.

The next stage in the evolution of the watch was mass-production techniques, used by the British Watch Company by 1843. An American company was making watches with interchangeable parts by 1851. During this industrial revolution period, it became fashionable to be on time to engagements, since only rich people had accurate watches. The standardization of parts and the invention of interchangeable components by watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet revolutionized mass production, making watches more accessible to a wider audience.

In 1904, pioneering Brazilian aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont needed to be able to see his watch without letting go of the controls with his hands in order to time his performances:

He asked Cartier to find a way to create a watch for his needs, and they designed one to be worn on the left wrist, with what are now called lugs to hold the strap to the case and a clasp to hold it firmly (unlike a slip-on women’s bracelet), a winding mechanism on the right, and a minute hand. They named the model the “Santos”:

. . . and it has been the basis of the majority of wristwatch designs since that time. This began the big transition from pocket watches to wristwatches, initially for drivers and aviators, which was continued for military needs . . .

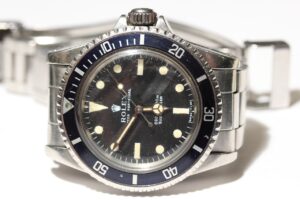

By the end of the 19th century, officers from Europe were using wristwatches to synchronize military actions. Early men’s wristwatches were pocket watches held in a leather wrist strap, but by the beginning of the 20th Century, wristwatches were being designed specifically for use by men, a significant revolution in watch design driven by the needs of the market. They were issued to all soldiers by 1917 and advertising watches for soldiers was commonplace. Brands like Rolex and Patek Philippe emerged during this era, solidifying their places as icons in the watchmaking world.

This image shows a watch with a detachable face guard, made around 1914 in England, issued to Private Percy Broady, 2nd Battalion, Auckland Infantry Regiment, worn during the war:

Wristwatches became popular with the public after the war, including the “tank” design by Cartier, inspired by the shape of the newly invented military machine.

Further Development of Wristwatches.

As watches became popular and available to the general public after the first world war, being on time became a symbol of having attained the status of being a reliable, middle-class person.

The evolution of the watch continued with automatic (self-winding) wristwatches being invented in 1923 in Britain (although the mechanism had already been available in pocket watches for two hundred years). Watches were also increasingly being bought by women at around this time, and used as a symbol of their independence.

In 1926, Rolex released their Oyster model:

. . . which was the first water-resistant watch, thanks to its screw-down case-back, screw-down crown and a screw-down bezel for the crystal.

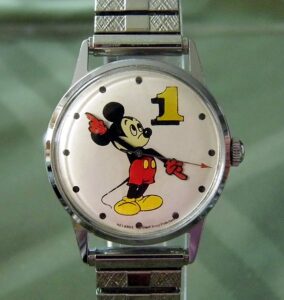

Wristwatches became more affordable, and thus more popular during the 1920’s and ’30’s. New features like the chronograph were added to some watches. The first Mickey Mouse Watch was launched by Disney, in 1933, available both as a wristwatch and a pocket watch:

The 1940’s and 1950’s saw watchmaking technology progress further, such as the introduction of new materials like stainless steel. Some watches became more complex, with sub-dials and other complications.

The electrical driven pendulum clock had already been invented back in 1921, using the vacuum tube oscillator invented nine years earlier, and was a huge step forward for scientific timekeeping. Electronic timekeeping took until 1957 to reach wristwatches, when the Hamilton Watch Company of Lancaster, Pennsylvania released their Hamilton Electric 500:

It combined battery-power (so didn’t need winding at all) with a complex traditional mechanical watch balance wheel and gear train, but rapidly became obsolete as technology moved forwards.

A few of the early electronic watches used a tuning-fork concept to keep time:

. . . such as the example above “Bulova Accutron Electronic Tuning Fork Watch, Model 214, The Watch That Hums”, but a few years later, a much more reliable timekeeping method was invented, which was to lead to one of the biggest revolutions in the watch industry . . .

On Christmas day 1969, after 10 years of development by their daughter company Epson, a new type of watch hit the shelves . . . the Seiko 35 SQ Astron:

It was, at the time, the world’s most accurate wristwatch, accurate to within two seconds a day, many times more accurate than the best mechanical watches at the time. It also had no moving parts, eliminating the need for regular cleaning, and making it more shock-resistant than other watches.

This was the first ever quartz watch, using the vibrations of a quartz crystal counted by electronic circuits to measure time, and it was the beginning of . . .

The Quartz Crisis, and Aesthetic Developments.

The early quartz watches were very expensive, and the Swiss watchmaking industry used the innovation in its high-priced watches. But Asian watch brands were making available much more affordable quartz watches, which became very popular, losing the Swiss watchmakers, who were still only applying the technology to expensive timepieces, their dominant position in the industry. They eventually followed suit, releasing their own relatively affordable quartz watches, preventing any further loss of market share.

At the same time, visual aspects of watch design became more adventurous, with brands like Omega, Rolex, and Breitling releasing more colourful and unusual watches, aligning with the trends in the market of the time, such as the psychedelic fashions. An example is the Breitling SuperOcean Chronomatic, launched in 1970 (below). Although the bright orange hands are nothing out of the ordinary now, they were radical at that time (and another of their watches features in our blog post about unusual watches, and is notable for a very different reason):

In Mara Cappelletti’s beautifully illustrated book, “The Style of Time: The Evolution of Wristwatch Design”, she says that, since the late ’70’s, the investment market for watches saw immense growth, Cappelletti reports. “Watches have hugely increased their value through the years.“ Collectors were starting to buy watches as investments, knowing that, if they made the right choices, the value of the timepieces they owned would rise.

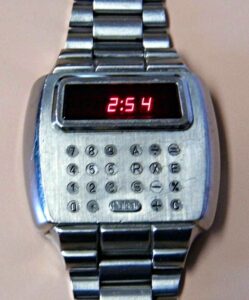

And, of course, during the ’70’s, another big step in the evolution of the watch took place. The Pulsar, which was the first LED electronic digital watch launched on 4 April 1972, making it a significant revolution in watch design, but it was expensive:

Low cost digital watches appeared three years later.

Around 1980 the calculator watch first appeared, from brands like Pulsar, Seiko, Hewlett-Packard and then Casio. These included a stylus to push the tiny buttons. This Pulsar Calculator Watch is said to be “the first calculator watch in the world”:

Continuing the exploration of colours and new design influences, Swatch (who’s name came from the concept “second watch”), released very affordable brightly coloured watches with bold designs, which related to a much earlier concept of wristlet watches, worn for fashion. They are also notable for having collaborated with many artists to produce unique looking watches with an interesting story, which was becoming an increasingly important factor in marketing a watch. I’ve written a blog post which looks at some of those interesting art collaborations by Swatch, and other watch brands.

Mechanical watches resurged in popularity during the 1980’s and ’90’s, with high-end brands like Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, and Vacheron Constantin introducing interestingly innovative designs. In these decades, watch brands also collaborated with other industries like Formula 1 and aviation as well as other brands, helping give some watches a noteworthy story.

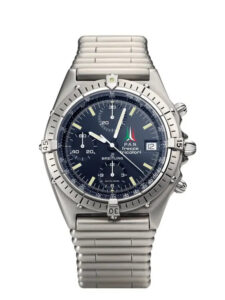

For example, Breitling created this watch for the Italian Frecce Tricolori Jet team, who wanted a new watch for its pilots, sturdy, comfortable, stylish enough to be worn with a suit, and analogue. They created a new mechanical watch for this purpose, with a slightly recessed crystal and innovative bezel to protect against the common problem of watches being broken when opening an aircraft canopy after landing. Their “Frecce Tricolori,” was presented to the Italian Jet Team in 1983:

The evolution of the watch included further technological advances, such as ever more accurate watches. Some designs used radio signals from government atomic clocks to regularly correct the slight inaccuracies in their quartz timekeeping. Quartz technology itself increased in accuracy, often by using increasingly higher frequency oscillations, with a Citizen Watch in 2019 having an accuracy of within a second a year, from a 8.4 MHz crystal, and by utilizing adjustments made every minute. An even more accurate watch was actually available before this . . . Bathys Hawaii introduced their Cesium 133 Atomic Watch around 2014, which used internal atomic timekeeping to maintain an accuracy of one second in a thousand years, it was a huge rectangular box on one’s wrist, but revolutionary.

Watches also experimented with connectivity, such as the Linux Watch in February 2000:

And the SPOT watch, released in 2004, which made news, weather, stock prices and sports scores and more available on the wrist, from radio signals, but new product development ceased only two years later. The Ruputer by Seiko, a computer on the wrist, was launched even earlier, in 1999.

But it wasn’t until the 2010’s that the concept of the smartwatch really took off, integrating functionalities beyond timekeeping, such as fitness tracking, communication, and entertainment. Brands like Apple, Samsung, and Garmin became prominent players in this burgeoning market.

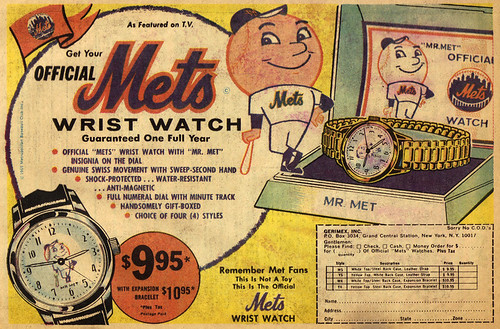

The Evolution Of Watch Marketing

Marketing as such is a relatively recent invention. The industrial revolution resulted in supply outpacing demand for the first time for most types of products. Before that, anyone making something which worked well, would consistently have more demand than they could supply, through word of mouth, so marketing and advertising was unnecessary, and indeed counter-productive since it, in effect, announced that the product was not good enough to get attention through word of mouth.

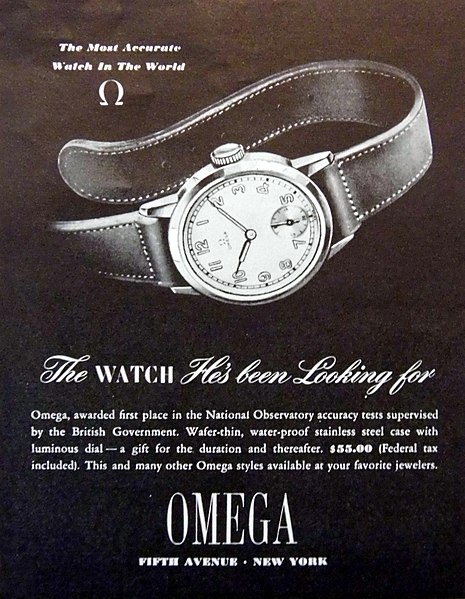

Watch marketing was often initially for relatively affordable timepieces for men, and focused on functionality and sometimes expensive materials such as gold for more upmarket watches.

In this era, wealthy individuals who wanted luxury watches would still rely on word of mouth to inform their choices, so watch advertising wasn’t aimed at such people.

Today, watch marketing is often about the beauty of engineering as an achievement in its own right, rather than for the accuracy telling the time. For example:

The HM9 Sapphire Vision from MB&F:

. . . is visually extraordinary as well as being technically impressive and a great example of watchmaking by a dedicated individual, and was made available to the public in four limited editions, with just five pieces each. Made as “a tribute to the extraordinary automotive and aeronautic designs of the 1940s and 50s. The result was a case like no other that echoed the epoch’s flowing, aerodynamic lines.“

Mechanical watches have a place in the current market even though they are less accurate, since everyone has the exact time on their smartphone anyway.

Watches are now much more about uniqueness and innovation, and have a lot of focus on the story, meaning and context of a watch. This is desired by the market when done for good reason and being intrinsic to the watch design, but sometimes done as a mostly irrelevant addition to a watch for marketing purposes, which, understandably, is disliked by enthusiasts. I explore this topic in my blog post on the love/hate relationship with limited-edition watches.

There is also an increasing focus on environmental concerns and sustainability, especially with wood watches such as this beautiful example from Vejrhøj which uses ethically sourced wood:

Recent watch ads also sometimes present watches as works of art, created by an individual expressing abstract concepts, which, while not always particularly true, points to an evolution in the desires of the market, from functional engineering for accurate timekeeping, and sometimes expensive materials, towards concepts from fine art rather than product design. I explore the authentic definition of “art” and how it applies to watchmaking, in my blog: Are watches art?

Watch marketing has evolved along with the desires of the market, which itself has been shaped partly by the changes in technology both directly, and in the way it results in increasing comfort, leisure time, disposable income and interests beyond survival, towards well-being and self-worth, rather than just being functional as a member of society.

Factors Behind Contemporary Watch Design

Some current watches are based on the story of important events, celebrities or specific watches from the past.

As I said near the beginning of this article, watches have always been made for people to purchase, but more recently some examples can be seen as a personal creative exploration. And, as I said above, some watches are now being marketed as if they were personal creations by an individual, even when that is not particularly true, because story and concept is a significant part of what sells watches, and because art is generally more valuable than product design for utility.

There are watches now being described as “like wearing art on your wrist”, even though their influences are mostly the same fine-jewellery and concepts of mechanical engineering design for mass-production that are the influences on most watches, making them clearly art not design.

As I mentioned above, with everyone having the exact time, as well as alarms and other functions, on their smartphone these days, the watch market now desires attributes beyond timekeeping, with a few watches now not even telling the time at all. Other watches are making use of recent innovations in technology, by incorporating various results of algorithmic design in their creation.

One of the biggest desires of the current market is uniqueness and individuality (I look into the reasons behind this, in my blog post on uniqueness). So that’s what the watch market often says it provides, sometimes very legitimately, but sometimes doing things like offering a “new limited edition” watch which is exactly the same as another of their models just with a slightly different coloured dial, which is, correctly, seen as just a marketing ploy.

Engineering innovations are now more likely to be used as impressive feats in their own right, or as aesthetically beautiful creations, than for practical reasons. An example is the Van Cleef & Arpels Midnight Planétarium:

. . . which shows the locations of each planet in real time . . . undeniably impressive and beautiful, but no-one would see it as a practical necessity, for most of us, at least.

The majority of the most unusual and interesting watches in the current market still have engineering as their most obvious aesthetic design influence, even when it is innovative and beautiful engineering. Here are some great examples:

Devon Watches Tread 1

The Devon Tread 1 uses a patented system of interwoven time belts to display the time. Its creativity is outstanding both from a technical point of view and from the perspective of the aesthetics:

The Richard Mille RM 70-01 Tourbillon Alain Prost:

. . . is a great example of their creative mechanical design, designed to reflect Alain Prost’s interest in cycling by including their “totaliser” which displays the overall distance travelled on his cycles. It was released as a limited edition of 30 pieces.

The Xeric Vendetta X Automatic:

. . . was “born from Mitch’s passion for vintage dystopian science fiction and concept cars of the 70’s like the Lamborghini Countach or Bond’s Lotus Esprit submarine“. It uses a wandering hour complication with a body inspired by aerodynamic shapes and a minimalist dial, making this a unique aesthetic watch for their 10th anniversary.

There are also some watches making great use of collaborations with fine artists, such as:

Blancpain, Métiers d’Art, The Great Wave.

This beautiful dial uses semi-transparent volcanic rock known as silver obsidian from Mexico as the background, and white gold patina for the applique waves, and was inspired by the famous Japanese woodblock print “The Great Wave Off Kanagawa,” by Hokusai.

Swatch has had a large number of collaborations with artists, including the example above.

More examples of watches with artist collaborations on my blog post here.

There is also an art jewellery influence on a number of contemporary watches, which can be seen in their use of complex, organic forms and rough surfaces, unlike the simple geometric shapes and smooth polished surfaces characteristic of fine jewellery (read my article for more on the characteristics of art jewellery).

Which brings me to our UnconstrainedTime watches. They are, arguably, the first watches based on what can be called conceptual art jewellery (rather than being based on existing watch design principles with some influence from that area).

One of the reasons that my watches are unusually unique, is that I am not, like the majority of designers of unusual watches, starting from a basis of conventional watch design then pushing the envelope from that starting point . . . I have no training in watch design, and many traditional watches are not a good fit for my personal aesthetic tastes. I am coming from a background in fine art and contemporary music composition, creating sculptural forms as a personal exploration, finding that my innovative simplified time-display allows me the creative freedom to come up with aesthetics-focused concepts which, after I’d made them, I was happy to discover align with the market’s desire for uniqueness and creativity. (More on my journey as an artist/creator, here).

Our UnconstrainedTime watches can be seen as a new branch of horology, a synergy of art with ancient time-keeping concepts. More details about that, on the Our Story page.

Our watches make sense as part of the world of conceptual art jewellery, which is art rather than design. If they were larger, they would be easy to see as sculptures (which have been an accepted part of the fine art world throughout its history):

Don’t miss our launch!

. . . make sure you subscribe to our Priority List for notifications.

What is your favourite watch which shows the evolution of the watch industry? Let us know in the comments below or on our social media.

Author: Chris Melchior

This article was authored by Chris Melchior, founder of UnconstrainedTime and creator of the original range of wrist-worn sculptures of this unique artistic adventure.

Chris has extensive knowledge and experience of creativity, including fine art and cutting-edge contemporary music composition, and was awarded a First Class Honours Degree in fine art and music with a minor in philosophy.

Chris’s life-long artistic obsessions include organic forms and textures, abstraction, fractals, and the aesthetic essence of musical genres.

He has developed unusually deep insights into the elemental concepts underlying areas including Eastern and Western philosophies, science and technology, creativity and the arts, as well as empirical spirituality in which he is acknowledged as a leading authority.

He has a profound fascination and love for the unique and synergistically creative combination of fine art with the ancient essence of time-keeping which evolved into the UnconstrainedTime project.

Leave a Reply