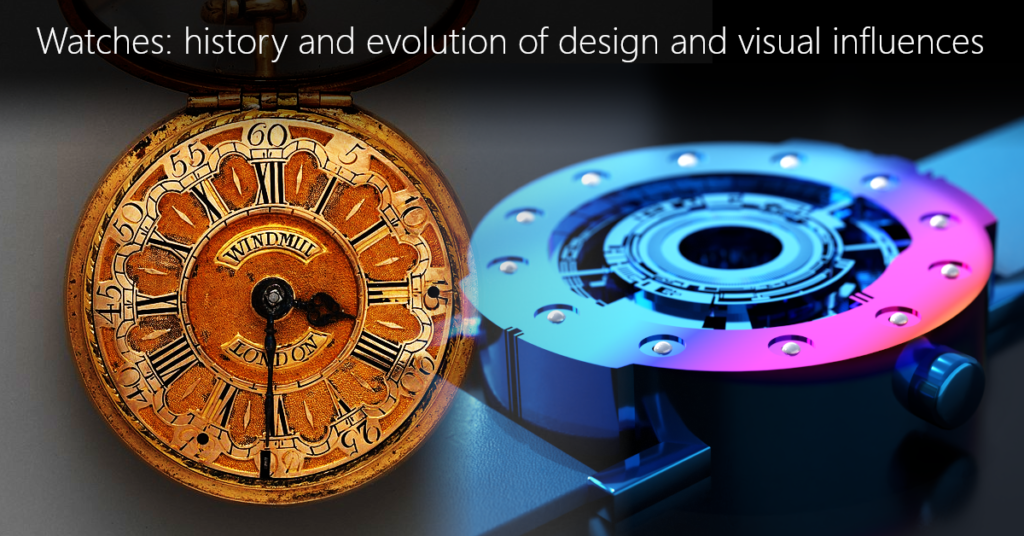

The image above shows the UnconstrainedTime Techno-circle #1 watch on the right.

Introduction

To understand the subject: “watches: history and evolution of design and visual influences”, you first need to look at the history of timepieces, watches and wristwatches, then at relevant areas of social and aesthetic influence . . .

This article investigates the following topics:

- Watches: history and evolution of watch design and aesthetic influences

- The history of fine jewellery and its aesthetic influences

- Art jewellery: aesthetics before functionality

- Relationships between functionality and aesthetics in watch design

- The first conceptual art jewellery microbrand?

This article starts with areas which are relatively well known and agreed upon, continues with some topics which are little known and/or controversial, and ends with a look at a significant new area of watch design which is entirely new at the time of writing.

Note . . . I only use watch images with permission from the watchmaker (unless the photos are public domain or creative commons), so some of the watches I present here might be lacking an image.

Watches: history and evolution of watch design and aesthetic influences

The history of timepieces

The earliest timekeeping devices measured time using continuous processes like water running from one vessel to another, the movement of the sun, or the burning of incense.

The ancient Egyptians divided the day into twelve periods, using their water clocks to determine when to start religious ceremonies.

By the 13th Century, artisans were building weight-driven clocks for cathedrals and churches in France and Italy, used for ringing the bells at the correct times for prayer. At this time, clock-keepers were paid significant sums of money to keep clocks accurate, which needed basic understanding of mathematics, in an age when education was rare.

The image below is of the clock in Salisbury Cathedral, made in about 1386. It is said to be the oldest clock in the world which is still working:

One of the most accurate early timepieces was the hour-glass, with a version called the marine sand-glass being the optimum way of measuring time at sea in the 14th century. The hour-glass visual symbol is still used to represent the passing of time.

By this time, mechanical clocks were also starting to be made. They became a status symbol, both for individuals and for towns and cities where clocks were prominent landmarks. An examples of this is the beautiful Prague Astronomical Clock (made in 1410), the most famous clock from the Medieval period, shown below:

Mechanical clocks used oscillating mechanisms, such as the swinging of a pendulum (used from the mid-17th century), which resulted in increased accuracy, helping facilitate trade, communication and travel. Some clocks made at this time, such as the one below, were highly decorated, showing that they were designed for well-off people.

The electric clock, invented in 1840, incorporated the most accurate pendulums available at the time.

It was only in the mid 19th Century that time started to be standardized between different locations, as was needed for railway services and telegraph operation. Before that, time was a more local phenomenon, since it didn’t matter if the time agreed upon in one city was somewhat different from the time agreed upon in another, with differences often being due to differing social, political or religious factors.

Mechanical clocks were the optimum method of measuring time until 1969 (according to this detailed article on the The birth of the quartz timepiece), when quartz timekeeping mechanisms were invented, using the piezoelectric effect to produce resonance in a quartz crystal resulting in precise oscillations, counted electronically. By the 1980’s, this was able to be achieved using solid-state (semiconductor) devices.

The history of watches

In the 14th century luxury portable clocks began being made. By the 16th century, these became small enough to be worn as pendants or attached to clothing.

The first mechanical pocket watches were made in the 17th Century, in Germany.

This image shows the movement, including balance spring, of a watch made by Thomas Tompion in about 1677:

As accuracy improved to around ten minutes per day, the minute hand was added to some watches, starting in 1680 in England. Improvements in manufacturing methods around the same time allowed an increase in the volume of watch production, although finishing and assembling was still done by hand until around a hundred years later.

This image is of an early 18th century watch, made in London:

Accurate timepieces were essential for measuring longitude at sea. In 1714, the British government offered a longitude prize (still offered today, although the scope of what qualifies, is wider) for a method of determining longitude out of sight of land, with the awards offering the equivalent of $2.5 million to $5 million in today’s terms. This prize is still going today. Here are fascinating details of Origins of the Longitude Prize. This resulted in much more accurate timepieces called marine chronometers, such as this example by John Harrison (between 1761 and 1800. Great Britain.):

17th and 18th Century watchmaking was dominated by the British, with most of the production being of high quality items for the elite.

By 1843, the British Watch company was using mass-production techniques (if you’re interested, I have a blog post on British Brands (including watches)). An American company was making watches with interchangeable parts by 1851. During this industrial revolution period, it became fashionable to be on time to engagements, since only rich people had accurate watches. The common availability of watches also had a profound impact on transportation.

Most watches were mass-produced after this time, and even now luxury watches typically use mass-produced movements, even if some of the other parts were made by hand.

Watch logos were also developing at this time, from their origins in names and family crests, to being more about marketing and brand identity. See our blog post “Watch Logos: How They Work: Their History, Evolution, Meaning And Design”

Wristwatches

. . . were initially worn by high class women such as Elizabeth 1 who was given one (described as an “arm watch”) in 1571, and were made to be more decorative than functional (their accuracy was poor). During that period of history women were expected not to know the time.

By the end of the 19th century, officers from Europe were using wristwatches to synchronize military actions. Early men’s wristwatches were pocket watches with a leather wrist strap, but by the beginning of the 20th Century, wristwatches were being designed specifically for use by men, a significant revolution in watch design.

The first world war saw wristwatches used for the timing of manoeuvres such as the “creeping barrage”, some designed specifically for rapid access during trench warfare (which pocket watches didn’t provide). They were issued to all soldiers by 1917. Wristwatches became popular with the public after the war.

This image shows a watch with a detachable face guard, made around 1914 in England, issued to Private Percy Broady, 2nd Battalion, Auckland Infantry Regiment, worn during the war:

Automatic (self-winding) wristwatches were invented in 1923 in Britain (although the mechanism had been available in pocket watches for two hundred years), with electric watches which didn’t need winding appearing from the 1950’s.

Watches were also increasingly bought by women at around this time, and used as a symbol of their independence.

Quartz (electronic) watches, ten times more accurate than those using mechanical movements, were introduced from 1969.

The Pulsar, which was the first LED electronic digital watch launched on 4 April 1972, making it a significant break-through in watch design, but it was expensive:

Low cost digital watches appeared three years later. LCD time-displays, which used much less power so were able to display the time continually, were available starting in 1974.

The 70’s also saw a large increase in the number of limited-edition watches available. For my comments on why some limited-edition watches are loved and others are hated, see my blog-post on limited edition watches.

Smartwatches appeared from 1994.

Some current luxury watches use mechanical movements, designed as collectible items, valued for their aesthetic appeal and links to the past even though they are much less accurate and more expensive than those with quartz timekeeping.

For some additional perspectives see our blog post on how the development of wristwatches relates to society.

Watches as fashion.

While the main purpose of most watches until the 20th Century was the time-display function, through most of that time, the most effective timepieces were expensive, and so only within the reach of rich people.

Gold and silver, as well as ornamental techniques, were often used in making timepieces. Some watches also had “complications” which refers to additional functions.

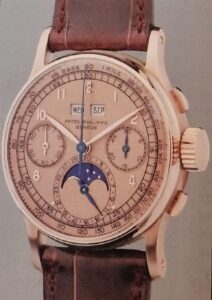

Here is the Perpetual calendar watch by Patek-Philippe, one of the earliest watch brands:

Some timepieces were designed more for aesthetics than functionality, such as very early wristwatches, which were for women and much less accurate than pocket watches used by men at the time.

Some expensive watches are currently designed to exhibit miniature mechanical technology as an achievement. Others incorporate expensive materials or added decoration.

These days, watches are often used to express one’s personal style and aesthetic preferences, as well as being status symbols.

Luxury watches

The concept of luxury goods can be seen as things which are desirable but not necessary. However, the term only applies to things which have some degree of functionality. By contrast, the term is meaningless in fine arts, even though they can have as much of a price differential.

The first luxury watch brand was Patek Philippe, which was founded in 1839.

One of the reasons that there’s a strong relationship between watch design and fine jewellery, is that when women began buying more luxury watches in the 20th Century, it was natural for watchmakers to combine watchmaking with the fine jewellery influences (see below) already known to be popular for women, but not used much in items for men, at that time. Through most of their history, most timepieces could only be purchased by the elite.

Luxury watch brands like Rolex and Omega began to emerge during the 1920’s and ’30’s, offering high-end timepieces. The 1960’s and 70’s saw a shift towards more colourful and adventurous watch designs, as well as experimentation with bold colours and shapes.

The 2000’s saw further innovations including use of materials such as sapphire crystal, and carbon fibre used in the watch below:

In today’s society, luxury watches are used to show one’s aesthetic choices, in addition to being a status symbol, and are sometimes bought as investments.

Timekeeping and society

Time-telling has been of great significance throughout history, from marine chronometers, through watches used to coordinate military actions, to the necessity of time-keeping accuracy for Global Positioning Satellite systems to function.

In the mid 14th Century the clock face was developed, adding time-indication to the main function of clocks which was, at that time, to ring bells at set times for prayer, providing regularity as a refuge from a chaotic and challenging world. The face had a single hand, often being a literal carving of a hand pointing at the indications.

Time has been such an important part of society, in many ways. Benjamin Franklin said, in 1748, “Remember that Time is Money.”

Some historians regard timepieces as more important in the origins of the industrial revolution than power looms and telegraph machines. For example, in his 1934 book “Technics and Civilization”, the author, Mumford, explains why, in his opinion “the clock, not the steam-engine, is the key machine of the modern industrial age.”

Different societies have different attitudes to punctuality, such as in Japan where being on time is a sign of respect, compared to being “fashionably late” for high class social events in some Western societies during specific periods, at the same time that workers were expected to be on time.

Organizing one’s life by time went along with the move from rural to urban environments and most people being employees.

An example is this is an early 20th century clock used to keep track of employee’s work hours. Each employee would dial the handle to their employee number on the face and push the lever. The device would encode and print the day, time, and employee number onto a paper roll.

Conventional watch/clock dial and hands are a very strong archetype, due to the increasing importance of time as societies developed throughout history.

It could be said that the 7-segment display relates to the even stronger archetype of numerals. Its relationship to space age design had some degree of aesthetic influence on watch designs which used it.

These powerful archetypes are strong influences on watch design, and, along with fine jewellery (see below) have acted to keep watch design in a strong relationship with its history, until now (see below for why and how that has changed).

The history of fine jewellery and its aesthetic influences

The real origins of jewellery, and what is incorrectly called “ancient art” are actually as receptacles for specific spirits, used for magick (i.e. influencing reality, as distinct from magic which is illusions and deception).

Different shapes and different materials were used to house different spirits, which were called into the receptacles during specific ceremonies. This practical functionality of what is often misunderstood as “decoration”, is still in common use today in many areas of the world, for example in the amulets used in Thailand, and African “sculptures” etc.

While Western writers tend to label such uses as “pagan superstition”, various talismans, amulets, and other objects with observable spiritual properties were in common use in the Abrahamic religions in the past (click here for the Wikipedia article on that), with some still being used today.

Copper began being used in jewellery about seven thousand years ago. Before that, shells, stones and bone were used. Metals had spiritual significance in early societies, as can be seen from the term “black smith”, which refers to metalworking as relating to the lower, darker end of spiritual reality.

Fine jewellery is still, today, valued because of the materials it uses (multiplied by the brand value), unlike art jewellery, which is valued as art (see below). This includes the precious metals and gemstones that are the “fine” in fine jewellery, which can be an investment, as explained in this article: “Good Investment: What Makes Jewellery Rise in Value?“

Some types of jewellery can be interpreted as originating from a mundane functional basis, such as buckles, brooches or hair-pins, while sometimes including more expensive materials and workmanship in their design.

Jewellery was sometimes used for storing personal wealth on the body, and this is still common in some cultures, such as the use of gold necklaces in India.

Jewellery is also often used to denote social status, as well as being used to signify affiliation to a group (such as a Christian crucifix), to denote some personal meaning (such as engagement (see the image below) or marriage), as an expression of personal style and aesthetic taste, or as an investment.

Jewellery often has strong cultural significance (originating in traditions of spiritual functionality, later becoming symbolic). For example, some cultures prohibit the use of some types of jewellery for some types of people, such as laws in ancient Rome dictating that only specific classes were allowed to wear some types of jewellery. Some cultures have specific types of jewellery as common displays of affiliation and status, such as “bling bling” in hip hop culture.

Since well-off people were the customers for both jewellery and watches, and some of the artisans and techniques used to make them were common to both, there are strong links between watches and fine jewellery.

The vast majority of jewellery is now classed as “fine jewellery” to distinguish it from what can be called “art jewellery”, which is a relatively recent phenomenon (see below).

Fine jewellery (and fashion/costume jewellery which imitates it with less expensive materials) mostly uses simple geometric shapes. This partly originates from the contrast between the rough, chaotic, organic nature of the material world and pure, perfect, symbolic shapes representing spiritual ideals.

There were also some practical reasons for fine jewellery using smooth shapes, for example, so a pocket watch didn’t catch on clothing.

A sub-type of fine jewellery, called ‘High jewellery’ or ‘Haute Joaillerie’ refers to top quality craftsmanship, finest quality metals and gemstones, applied to watches such as the example below:

Recent techniques such as 3D printing have made changes to what’s possible in the world of jewellery (and watches), and creations by artisans, as well as artists, are increasing in popularity.

Art jewellery: aesthetics before functionality

Different areas of art jewellery include contemporary jewellery individually made by studio craftspeople, and conceptual art jewellery which is fine art (where concept and aesthetics are primary) rather than craft or design by an artisan.

Art jewellery is usually created by an individual, in contrast to fine jewellery which is typically designed by committee and mass-produced.

The history of the subject begins with the arts and crafts movement originating in the 1860’s, then relates to Art Nouveau from the 1890’s as well as modernist jewellery in 1940’s America, followed by the 1950’s experimental work by German goldsmiths. It also relates to the concept of fine art, which can be seen as having its origins in Europe a few hundred years earlier.

Art jewellery can also be seen as a reaction against fine jewellery, with art jewellery sometimes using materials of little value, and exploring things like rough textures and complex, uneven or broken forms which would be unacceptable in the world of fine jewellery with its emphasis on simple, perfect geometric shapes and smooth, highly polished surfaces.

This makes art jewellery part of what is by far the most significant revolution in the thousand year history of Western Art tradition (which few people are aware of).

This revolution is most obvious in music, which can be seen as a progression from very simple mathematical relationships between notes (which are symbols), through increasingly complex relationships between notes, to the point where the only possible progression was from notes to continual spectra (ambient music). i.e. from symbols to direct use of the reality of the natural sounds, in all their fascinating fractal complexity.

The same revolution in visual arts goes from a thousand years of representational art (i.e. art about things which function as obviously identifiable symbols), to abstract art which is about its own existence rather than being representing other things. And also from craftsmanship producing designs which align with the acceptability of the time, to the fine art process as personal exploration valued for innovation and creativity more than fitting in with what’s been done before.

This well-known painting, “The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, 1838 “ by J. M. W. Turner, is an example of a painting which is almost abstract, just retaining a small identifiable object which was still necessary for artworks to be accepted until a few years later:

Jewellery, in the same era as abstract art and ambient music, goes from fine jewellery which is based on simple geometric shapes very much within a historically agreed system of narrow acceptable options, to art jewellery which often uses deliberately rough or broken (fractal) textures and is very much about the personal creative exploration, with the fine art process being used in what might be called conceptual art jewellery.

Here are examples of art jewellery:

For lots more examples, see our Pinterest board on art jewellery.

Art jewellery even sometimes abandons functionality entirely, producing items which cannot be worn on the body, conceptually similar to watches which don’t show the time, which relates to the fascinating question: “art watches art?“

The inevitability of art jewellery watches

The evolution of watch aesthetic influences is inevitably progressing from fine jewellery towards the possibility of art jewellery watches.

Early watch adverts focus on the properties of fine jewellery such as materials (eg. “18 carat gold”), and functional mechanics (eg. “keyless lever” or “extraordinary accuracy”).

Many luxury watches are now being advertised as if they have the characteristics of art jewellery such as being created by an individual focusing on chosen aesthetics, being influenced by art such as by embodying abstract ideals and having a lot of focus on story and concept.

For example, an online article talking about a luxury watch brand said that the watch “looks and feels like wearing a piece of art on your wrist.” In reality, these watches have little or no influence from anything other than the same aesthetic influences, of mechanics and fine jewellery, that almost all other watch brands have in common, and that includes most watches known for having creative design, making them clearly design rather than actually fitting the definition of art.

This development can be seen as part of the evolution of the arts in general, with the expansion into art jewellery watches being somewhat later than the move to abstraction in visual arts and the ambient revolution in music, all of which can be seen as the biggest revolution in the Western Art Tradition for more than 1000 years. The watch industry has often been slow to change (an example being the quartz crisis).

Societies can be seen as starting from relying on the natural world in prehistory, through periods of becoming civilized and rejecting nature, to more recently returning to an appreciation of nature, seen as “beautiful” and desirable for the first time. This parallels the evolution of the arts, as detailed above.

The limitations due to the major historical influences on watch design being mechanical design for functionality and mass production, and fine jewellery, are no longer the only option, especially in an industry where innovation is what a lot of customers desire. Some cross-fertilization between the watch industry and art jewellery can already be seen (detailed below).

Since everyone has the exact time on the smart-phone in their pocket these days, as well as other functions such as alarms and timers, it is easier for this significant new direction in watch design to place less emphasis on the time-display function of a watch, allowing much more focus on the watch as an art object, expressing the personal exploration of the creator and the aesthetic choices of the wearer.

Things are starting to change in the direction of art jewellery watches already . . . we’re starting to see some recent examples of art-jewellery influences, added to conventional mechanical watch components and shapes. These could be seen as examples of decorative arts, since they use art applied as an addition to a piece with otherwise functional influences.

Examples include those in my infographic on the art and art-jewellery influences on watchmaking, and:

The “khumeia” by Simon Pierre Delord, which has a significant influence from Art Nouveau, with conventional watch hands.

The Cartier Crash Tigrée watch has strong art-jewellery influence as well as some fine jewellery influence while retaining conventional watch hands:

The Molnár Fábry Architectural Art Piece:

. . . this unique and beautiful watch has an engraved dial inspired by Art Nouveau.

The Piaget Altiplano Rose Watch has a gold dial, engraved with a rose motif, which is some degree of art jewellery influence in a conventional case:

The DB28 XP Météorite by De Bethune:

. . . has a beautiful dial with a significant art-jewellery influence of irregular shapes and marks, with conventional case and hands:

Blancpain The Great Wave is a gorgeous art-jewellery dial inside a conventional fine jewellery watch case:

Art jewellery influence can also be seen in the way Holthinrichs watches proudly display the rough 3D printed texture on some parts of their watches:

Wood watches can be seen as belonging to some degree in the art jewellery space, since they use materials with organic textures, and which are not as valuable as precious metals. See my blog post for details of wood watches.

For more detail on how art jewellery relates to watchmaking, and the fascinating background to that subject, see my blog post on art jewellery and watchmaking. I have also written in more detail why it seems to me that art jewellery watches were inevitable.

Relationships between functionality and aesthetics in watch design

In this article we’ve seen how watch design, while being mostly based on functionality, has, throughout its history, had significant influences from fine jewellery.

The relationships between functionality and aesthetics in watch design are complex and interwoven, such as early wristwatches being predominantly an ornamentation for women, in between earlier and later watch designs very much for functional timekeeping.

Decorations are sometimes added, whether engraving, decorative gemstones (different from the small gemstones used in mechanical watch movements of “jewelled watches”), or materials specifically chosen for their decorative properties. As with the art jewellery influenced watches mentioned above, this defines them mostly as decorative arts, where artistic elements are added to a piece mainly designed for a function, as distinct from fine art which is primarily about aesthetics and not functionality.

An interesting concept, which can be used in both the functionality and the aesthetic design of watches is algorithmic design, which are sometimes used to create unusual watches.

There are many other interesting examples of unusual watches currently, but most of them have little or no influence from anything other than mechanics or fine jewellery, apart from a few examples having some degree of art jewellery influence, like those mentioned above. See some great examples of these unusual watches on my blog post: the evolution of the watch.

The first conceptual art jewellery microbrand?

We’ve seen in this article why timepieces look the way they do, up to this point in history.

Most of the unusual watches up to now have designs which are still mostly based on mechanical functionality and/or fine jewellery, with a relatively small number of recent examples having some minor degree of art jewellery influence.

Why ours look different.

Most people who start new watch microbrands are trained as watchmakers and/or starting from a deep love of existing, historically influenced, watch brands.

I am not either of those things . . . my main influences are fine art and contemporary music. So I was not approaching the creation of watches from the starting point of being a watchmaker, and the majority of current watches are not a fit with my personal aesthetic preferences.

Other authors have mentioned that the only difference between fine art sculptures and conceptual art jewellery is the scale. I will explain below why our watches are fundamentally based in the conceptual art jewellery space, as well as using an ancient horological principle.

It was only after I’d created some of my very unique and individual watches that I happily realized that they fit into concepts which are desirable currently, such as the thirst for innovation from microbrand enthusiasts, and the personal creative exploration of chosen aesthetics which is conceptual art jewellery (and which is the fine art process).

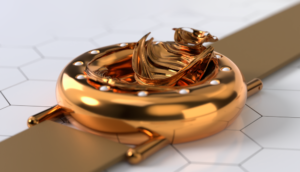

Unconstrainedtime is a conceptual art jewellery brand because:

Our watches (see below) are very definitely based on chosen aesthetics.

UnconstrainedTime’s radical innovation, creating a simple, small-footprint time-display with neutral styling, allows us to be, arguably, the first watch brand to focus primarily on chosen aesthetics.

Each UnconstrainedTime watch is by an individual creator, and is sold as a one-off or small numbered release, with the creator’s signature on the back.

The art jewellery used in our watches are not merely decorations added to a mechanical or fine-jewellery basis, they are the fundamental basis of the design of the whole watch, with the 12-hour a day concept of our time-display from ancient horology working effectively as an integral part of each piece.

Our watches use textures which are not part of the fine jewellery vocabulary, such as rough blackened silver, organic or fractal forms, or grainy 3D printed surfaces. They also use forms which are complex and organic, unlike the simple geometrical basis of fine jewellery.

Our watches are not only very individual, they are also very much a personal exploration by the creator (which is one of the main definitions of art). Some people love our creations, but they are definitely not for everyone. Like the abstract paintings that inspire us, our watches evoke strong reactions. They speak to collectors who think independently, who value genuine artistic expression, who understand that true creativity can’t be mass-produced. Our pieces become more than objects – they’re physical anchors to moments of choice, sparking conversations and marking significant chapters in their owners’ stories.

Our watches have a narrower appeal than those of most brands. We’re not trying to appeal to a wide audience (that’s what mass-produced watches are for), for the same reasons that most contemporary fine art has a narrow appeal.

It is clear from looking at them that the aesthetic influences on UnconstrainedTime watches are art and conceptual art jewellery rather than mechanical design or the traditions of fine jewellery. This is also reflected in the brush-strokes used in our watch logo.

All these factors together make it very obvious that UnconstrainedTime watches are part of the conceptual art jewellery (and fine art) space:

Don’t miss our launch!

. . . make sure you subscribe to our Priority List to receive notifications about our launch.

Do you think UnconstrainedTime watches are art jewellery? Let us know what you think, in the comments below or on our social media.

Author: Chris Melchior

This article was authored by Chris Melchior, founder of UnconstrainedTime and creator of the original range of wrist-worn sculptures of this unique artistic adventure.

Chris has extensive knowledge and experience of creativity, including fine art and cutting-edge contemporary music composition, and was awarded a First Class Honours Degree in fine art and music with a minor in philosophy.

Chris’s life-long artistic obsessions include organic forms and textures, abstraction, fractals, and the aesthetic essence of musical genres.

He has developed unusually deep insights into the elemental concepts underlying areas including Eastern and Western philosophies, science and technology, creativity and the arts, as well as empirical spirituality in which he is acknowledged as a leading authority.

He has a profound fascination and love for the unique and synergistically creative combination of fine art with the ancient essence of time-keeping which evolved into the UnconstrainedTime project.

Leave a Reply